SUDBURY -In the early hours of Dec. 21, 1931, at about 3:30 a.m., while on his rounds as car Inspector on the Canadian National Railway yards, Harold Haley discovered the body of 34-year-old Const. Albert Nault of the Sudbury Police Force lying face down in a pool of blood. A steel-jacketed, .32 bullet had gouged the officer's forehead and he fell where he was shot, slain in cold blood, on the platform at the rear of the CNR freight sheds.

When found, not only was the body lying face down, but both feet were together. Both arms were lying flat by the side of his body, palms upward, with his face lying right side up in the only patch of snow on the platform. The right hand was ungloved with his nightstick lying about four inches from him. Nault’s constable’s cap was also off, and lying under his left hand.

The investigation begins

Haley immediately informed the police department, which had already sent detectives Scott and McLaren on a tour of Nault's regular beat to figure out why he had not reported into headquarters at 1:30 a.m. as expected. Both detectives arrived on the scene shortly after Haley’s discovery.

“I had stepped between two freight cars along the east side of the platform and noticed the body immediately, not six feet from me. I telephoned the police station at once," Haley said at the time.

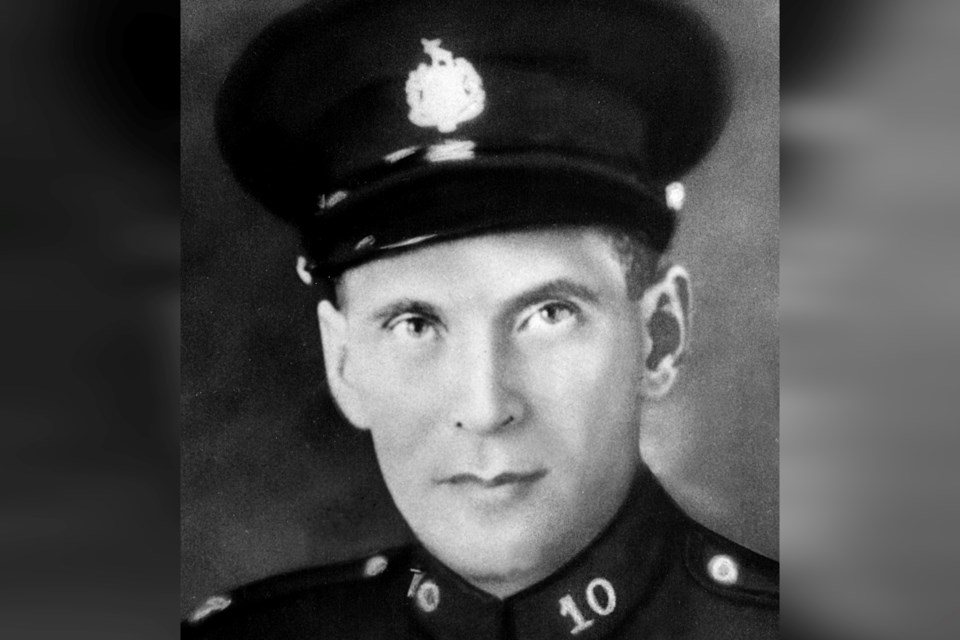

A man described by his peers as a conscientious and respected policeman, against whom there was no known grudge, Nault became the first member of Sudbury’s police force to meet death at the hands of a murderer. The absence of a motive, as the constable was killed while carrying out the regular routine of his beat, cast a deep fold in the shroud of mystery that blanketed this crime.

Not two hours prior, Nault had departed from his wife and four small children, the eldest, a girl of five, at their modest home on Burton Avenue, to begin what he believed to be another regular day on the job.

Now, Mrs. Loretta Dubois Nault, a small, dark-haired woman, was awakened at 5 a.m. by her parish priest, Rev. J. Waddell of Ste-Anne-des-Pins, to be told that she was now a widow due to a murderer's bullet.

Terrible news

“Mrs. Nault took the news very bravely," said Father Waddell. "As soon as I walked into the home, she knew that something had happened. She said. 'Oh, you've come to tell me something about my husband.’ I replied that I had and she inquired if he was hurt. I said, 'He is very seriously hurt.' She asked whether he was in the hospital and I told her that he wasn't. Then, she knew he was dead."

Mrs. Nault, with her little ones in tow, was brought to the house of her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Florian Dubois, on Jean Street, by Waddell as soon as he had broken the news to her.

“She was very courageous, and later confided in me that, while she did not exactly have a premonition of his death, she had lived in fear that at any time tragedy might befall her husband, as a policeman's life is a dangerous one."

"I could not realize it at first," Mrs. Nault stated in an extensive interview. “It was only such a few hours since he left, and he left singing and dancing. I called him at 10:30 Sunday night so he would be ready by 11 o'clock, and he jumped up and started the gramophone, and started to dance with me. He danced around, singing and fooling, while he was buttoning up his uniform."

As she recalled her husband’s dancing, while unknowingly preparing to go to his death, Mrs. Nault lost control of her voice. Although red-eyed from weeping, her tears passed quickly and she continued on showing little outward indication of the bleakness of her situation or her broken heart.

“What is the use of grieving?” asked Mrs. Nault. “Albert is gone, and that won't bring him back. The children can't understand (that) their daddy will never play with them again. When I tried to explain it to little Paul (two and a half years old), he just said, ‘Why can't Daddy play with me? Can’t he walk and talk any more?.’ He just can't believe he will never see his daddy again.”

Mrs. Nault also explained during her interview that when her husband came home from work, he always unloaded his gun so that the children would not get hurt. "I always loaded it for him after I called him (to get ready for work), and handed it to him the last thing before he left, and I did just the same last night."

While she spoke of her husband, her four small children: Eugenie (five), Noel (four), so called because he was born at Christmas, Paul (just under three) and Roger (10 months), played around the room, mostly oblivious to the tragedy that had befallen their once happy home.

“It will be a sad Christmas for them," said their mother. “We were getting ready for Christmas, but now …”.

As her interview wrapped up, Mrs. Nault recalled their six happy years of marriage.

Nault was born in Winnipeg (where his mother and 11 siblings still resided at the time of his death) and came to Chelmsford in the early 1920s.

“We were married at Chelmsford,” she said. "Albert was 28 and I was 19 when we were married. He was 34 on Sept. 6. We were married on Nov. 23.”

After living in Chelmsford for three years, they came to Sudbury, where on Oct. 4, 1930, Nault was sworn in as a constable of the Sudbury Police Force.

When the crime was discovered, provincial and railway police were notified immediately and before 4 a.m. a dragnet was out across the area. City police searched hotels and hangouts, and assisted railway police in watching trains, while an OPP detachment was rushed to Sudbury to assist.

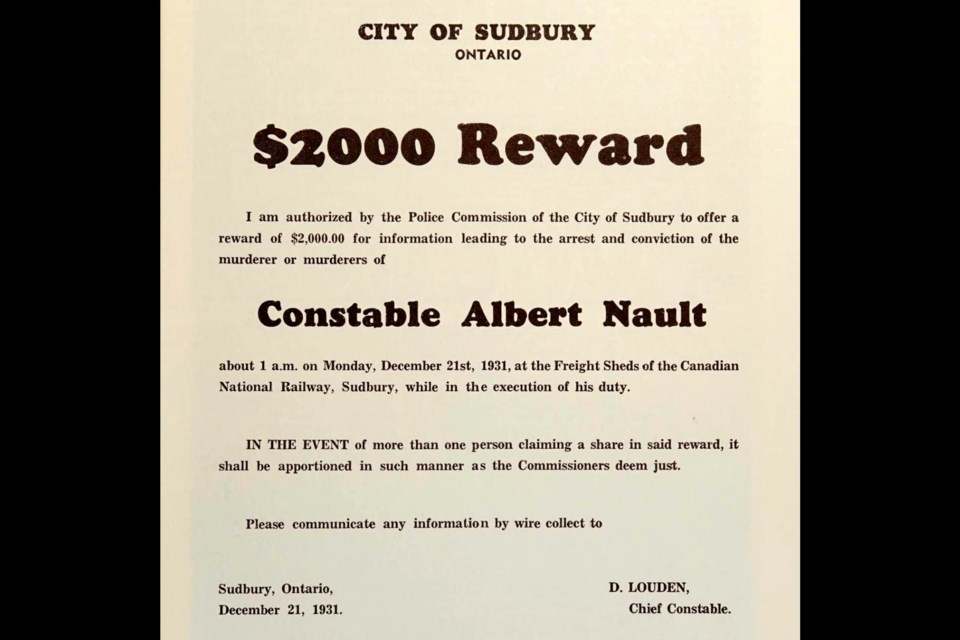

Police photographs of the body were taken before it was removed and taken to an undertaker, where a post-mortem examination was made by Dr. W. J. Cook. By noon, a reward of $2,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the murderer (or murderers) was posted by the Sudbury police commission.

Hunting for a murderer

The post-mortem showed that the constable had been killed by a .22 calibre, steel-jacketed, explosive bullet that burst into more than 50 pieces when it entered his skull. The shattered remains of the bullet were removed by Dr. Cook, and on instructions from the attorney-general, the pieces were sent to Toronto to be examined by a ballistics expert in an effort to trace the weapon from which they were fired.

Due to the fact that it was missing, it was initially believed that the constable had been murdered by a shot from his own gun, but since his weapon was loaded with regulation .32 calibre “long lead” bullets, it couldn’t have been Nault’s own weapon.

Police believed that Nault had been killed at about 12:46 a.m. and that he had no chance to defend himself. The theory posited was that he had walked along the west side of the freight sheds, then around the northwest corner of the sheds. There, he mounted a ramp onto the platform, passing within 10 feet of the end of a row of freight cars on a siding west of the platform. Then, he crossed the platform to try the lock at the door on the northeast corner of the sheds, removing his glove from his right hand as he did this.

As the moon was high and the night was clear, he most likely did not require his flashlight. When he turned from the door, to descend the ramp, he may have noticed something suspicious and stepped forward to investigate. There, lurking between the freight cars, the killer would have seen the officer drawing his nightstick. Then, as he saw him take another step, the murderer fired a single shot.

Nault fell with his nightstick still clutched in his hand. However, when his body struck the platform, the club would have been jarred from his grasp since it was found beside his right hand.

The murderer then slipped forward and reached inside the right hand pocket of the constable’s great coat, removing his revolver. Nault was known to carry it in his pocket and not in a holster. The culprit also took the constable’s flashlight, which would have been in the left hand pocket of his coat. Nothing else was touched. Money, watch and handcuffs were all left in the constable's pockets.

The time of the murder had been fixed at 12:46 a.m. by John Jones, the CNR night telegrapher. "I heard a bang like a gun going off, but I thought it was a car backfiring," he explained. “I had to check some cars between 12:30 and 1 and was walking along the tracks north of the station, and almost directly opposite the scene of the murder when I heard the report. I didn't think anything of it at the time and did not investigate. There are so many other noises that sound like a gun going off, and my view of the freight shed platform was blocked by some freight cars, so I didn't see anything."

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Allard told police that they saw Nault walking toward the CNR station at about 12:45 a.m. as they were driving past. They are believed to be the last people to see him alive. Joseph Dyell and his wife, who lived a short distance from the spot where the constable’s body was found, reported that they were awakened by what they thought was a shot some time before 1 a.m.

“As chairman of the police commission, I regret to inform you that Constable Nault was killed In the execution of his duty early today,” said Mayor Fenton at that night's city council meeting. "We thought in fairness to the wife and family that a reward of $2,000 should be offered for Information leading to the capture and conviction of his assailant. It was first suggested that we offer $1,000 but then we thought it should be higher."

That same day, a purse of $100 ($1,880 in 2024) was presented to Nault’s widow by members of the Sudbury Police Force, who had taken up a collection on her behalf. Another $190 ($3,572 in 2024) had been raised from among civic employees, which was to be given to her at a later date.

A “subscription” was also expected to be circulated among the citizens of the city in order to raise funds for the widow and four small children.

By order of Mayor Peter Fenton, the flags on all municipal buildings were also ordered to be flown at half mast, in tribute to the memory of the murdered constable, until after the funeral.

"Constable Albert Nault was one of the most conscientious officers of the force,” said Chief David Louden, paying tribute to the murdered constable prior to the funeral. "He had a natural aptitude for police work, which, coupled with a very observant nature, made him an excellent constable.

“On more than one occasion Constable Nault's powers of observance cleared up cases that might have gone unsolved, and at least twice that I recollect he brought in suspects that were linked with cues we were Investigating.

“He always carried out instructions to the letter, and I could give him instructions confident that they would be carried out in an efficient and praiseworthy way, and to the best of his ability. He seemed to enjoy his work. He took such a pride and pleasure in his job, that it was a pleasure for others to work with him. He will be greatly missed by myself and his fellow members on the force."

On Dec. 23, approximately 300 people attended the funeral at Ste. Anne-des-Pins Church. Even in the drizzling rain, a large crowd followed the funeral procession. Every member of the Sudbury Police Force, with the exception of two detectives, who were required to remain on duty at the station, attended the funeral.

At 8:30 a.m, the cortege formed outside the home of the father-in-law of the murdered constable, where the body had lain since the previous afternoon. Then at 8:45 a.m., the crepe-covered coffin was borne to the waiting hearse by six members of the Sudbury Police Force, including Sgt. Fred Davidson, who would be the city’s second murdered police officer just under six years later. Following the hearse were 21 cars bearing mourners.

On College Street opposite Sudbury High School, the Legion and Citizens' Band awaited the cortege, leading it from there to the church, playing the "Dead March from Saul," by Handel. High mass was sung by the same person who notified Mrs. Nault of the death of her husband, Rev. Fr. Waddel. The constable was buried at the Roman Catholic cemetery in the same uniform he was wearing when he was murdered.

Unfortunately, even while working feverishly day and night and calling upon every resources at their command, the police only uncovered one lead of any substance which, they hoped, would eventually solve the murder.

Early that Monday morning, between 12 and 12:30 a.m., a man dressed in black pants and a khaki colored coat with a light cap had entered a cafe on Borgia Street where he had a cup of coffee. At about 3:30 a.m., and dressed differently, he returned and ordered another cup of coffee, which he did not finish. He then left hurriedly, stating that he was immediately “going west.”

The man was described as approximately 32 years old, six feet tall, and weighing about 190 pounds. He had a dark complexion with black hair and spoke with an American accent. While there was nothing to specifically connect this man to the crime, his peculiar actions made him a possible suspect in the eyes of the police. Flyers bearing this description were even circulated amongst the police all over Canada and the border towns in the United States.

Never in the history of the city (up to this point) had public sympathy been stronger. It seems that every citizen in Sudbury thought themselves a detective trying to track down the murderer, because for the first two days after the killing, the telephone in Chief David Louden's office rang continuously as citizens phoned in “tips" they hoped would help the police to track down what was then the most cold-blooded killer to ever set foot in this city.

A thorough search of all hotels, boarding houses and any place where it was thought a murderer might hide, failed to yield any clues. And, throughout the first day of investigation, a constant stream of suspects were brought to the police station for questioning, but in every case the suspects were able to prove an alibi.

It was even thought for a short time that the murderer was about to be caught when reports came from Romford that two men had been seen skulking around in the bush.

A posse of municipal and provincial police were immediately dispatched and searched the area, but all that they found were three boys hunting rabbits.

Every lead, no matter how insignificant it looked, was tracked down, and investigated. Unfortunately, in the end, the murder of Constable Albert Nault would not only go down as the first homicide of a policeman in the city’s history, but also the only one that remains unsolved, nearly 93 years later.

Jason Marcon is a writer and history enthusiast in Greater Sudbury. He runs the Coniston Historical Group and the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page. Then & Now is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.