Dialogue and transparency.

Those words have served Kristan Straub well over his 22-year career with Glencore and the postings that have sent him across Canada and around the globe.

Earlier this year, the Sudbury-born Straub, the now-former vice-president of exploration with Glencore’s nickel team, was offered a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to advance one of the world’s new and untapped sources of critical minerals.

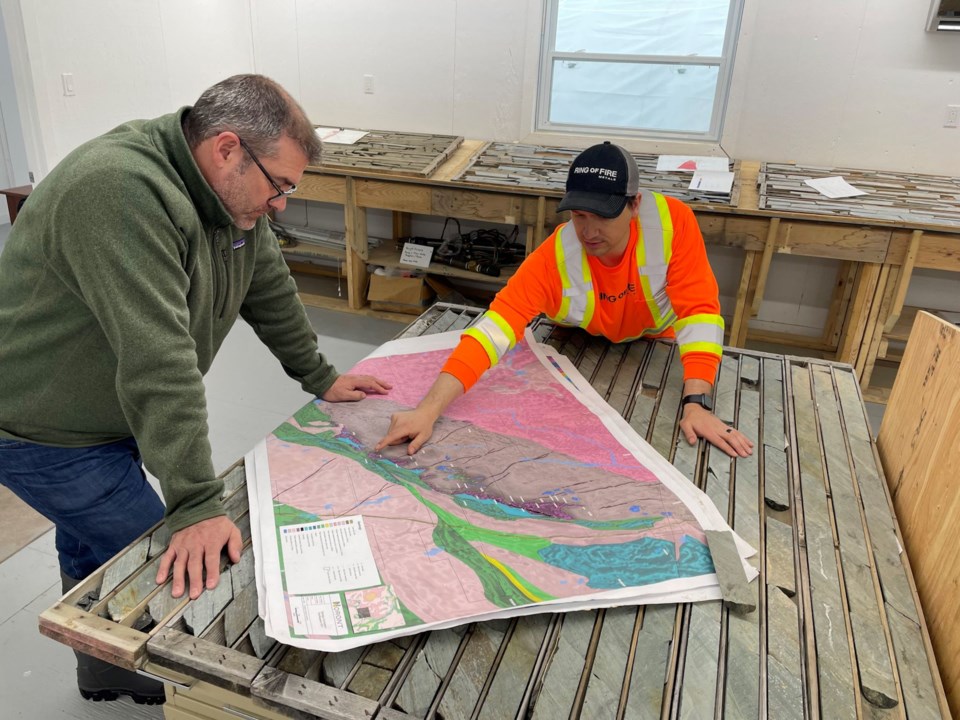

As the new CEO of Ring of Fire Metals, a Canadian subsidiary of Australia’s Wyloo Metals, Straub was drawn to the position to develop a “generational” mining project that would bring about “meaningful change” to the Indigenous communities in the James Bay region, a vast area of wetlands that has never seen industrial development.

“What enticed me was the quality of this project and the opportunity to actually build something from the ground up,” said Straub, a member of the Henvey Inlet First Nation in northeastern Ontario.

The company’s first mine in the batting order is the Eagle’s Nest nickel, copper, platinum group metals project. The start of construction and production is undetermined, pending the completion and approvals of the federal road and mine environmental assessments.

The mine project, itself, is designed to be carbon neutral on emissions and built on a strip mall-sized footprint of the current exploration camp. All the waste rock will be stuffed back underground in the mined-out voids.

But the Ring of Fire hasn’t been without its controversy in the 15 years since minerals were discovered. Some outlying communities surrounding the mineral belt remain outraged by the lack of adequate government consultation and harbour concerns that mining will be disruptive to their way of life.

Part of Straub's job will involve mitigating those concerns and demonstrating there can be a balance between industrial development and safeguarding the environment.

Straub acknowledges his Indigenous roots afford him a unique understanding of the sensitivities and inflamed passions of some communities.

As a Henvey Inlet band member, a progressive Georgian Bay community situated between Sudbury and Parry Sound, Straub is well acquainted with what proper and responsible consultation and collaboration looks like.

The reserve land is home to the largest First Nation wind partnership project in Canada. Its subsidiary, Nigig Power Corp., teamed up with renewable energy financier Pattern Canada to build and operate a 300-megawatt producing site and power line near Britt.

Born into a Northern Ontario mining family, Straub grew up in Falconbridge, a historic company town that's been amalgamated into what is now the City of Greater Sudbury.

His Swiss-born father, Hans, immigrated to Canada with his family when he was a boy and later worked at the Falconbridge (now Glencore) smelter.

His Indigenous mother, Anne, grew up in the Killarney area, is part of the Solomon family, a historic clan well known along the north shore of Lake Huron and down the length of Georgian Bay as far south as Penetanguishene.

Straub, trained as a project geologist, was with Falconbridge when the Nickel Rim South discovery was made in 2001 and later worked on the Fraser Morgan Mine project, two operations that are sustaining Glencore in the Sudbury basin today.

“What I bring to the table is a background in exploration through project development into operations,” said Straub.

As vice-president of operations for Raglan Mine in Northern Quebec, he was tasked with managing the impact benefit agreement – originally signed in 1995 – for the two host Inuit communities, Salluit and Kangiqsujuaq.

During his four-and-half year stint as head of Koniambo Nickel in New Caledonia, Straub said he maintained an open door policy through ongoing dialogue, being solution-oriented and in working with Indigenous people to establish service business.

He takes those experiences into this assignment.

Noront Resources, which was acquired by Wyloo, made great strides in building trust and goodwill with two nearby communities, Webequie and Marten Falls First Nations, at the earliest exploration stage.

The company signed memorandum of understanding agreements with both communities, which are leading the environmental assessments of the Ring of Fire mine and community road networks.

"I don't those would be possible if our First Nation partners didn't have transparency and understanding of how we intend to work as partners through this process," said Straub.

All the historic information on the project has been shared with the communities, he said. They know the company’s intentions and their mine development plan.

What Ring of Fire Metals can offer at this stage is opportunity, through procurement contracts.

Depending on the phase of development or operation, Ring of Fire Metals will be looking to source consumables, secure contractors and skilled workers involved in everything from environmental sampling and monitoring to heavy equipment and operators.

As for the outlying communities like Neskantaga and Attawapiskat, Straub said they continue to “maintain an open ask for dialogue.” The environmental assessment (EA) process for road access can provide a platform for discussion.

However, he adds, the community leadership’s calls for actions on basic amenities, like access is clean water, is not something a mining company can address but is the role of the federal government.

“I don’t think anybody is looking for bad tradeoffs (with road and mine development),” said Straub. “Today, the key element is outreach and engage in open dialogue to understand."