The purpose of residential schools was to eliminate all aspects of Indigenous culture. There is no other way to say it. But those who would impose their will underestimated the strength of a people who were deprived of the most basic of human needs: family, language, culture, security, even belonging; they did not see that everything they wished to eliminate could be (and would be) reclaimed, though the path is long and difficult.

It is reclaimed even in the smallest of ways, in ways that might seem inconsequential to those who have the privilege of only considering their hair as a fashion statement or a flattering attribute.

But hair is powerful. There are countless cultures that celebrate the length of hair; they see it as a seat of power, of the soul, of something that is sacred and should be considered almost as a limb, certainly a part of someone’s body, rather than an offshoot from it.

For instance, hair is of great importance to Orthodox Jewish people, who do not shave at the four corners of their face, and the removal of this hair, and thereby the removal of the Jewish identity, was one of the aims of Hitler’s Nazi Germany. The shaving of people’s heads was another insult upon an already inured and injured people.

The same is said of residential schools. The removal of Indigenous children’s long hair, so treasured by their people and not just rooted to their heads but to their sense of self, was among the first steps to removing their identity – but of course, under the guise of education, and salvation.

Other steps to erase and replace traditional culture continued from separating siblings so that they felt isolated and alone, to painful punishments for speaking their own language, and more, some too horrible to imagine.

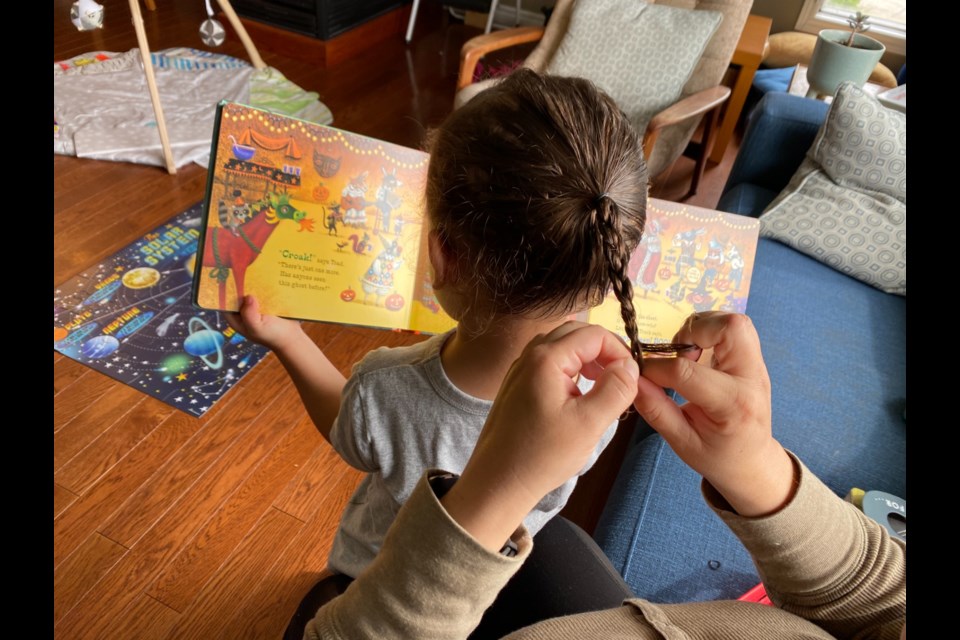

And while the fight for justice, truth and reconciliation continues, there are the small acts of reclaiming identity that can bring that sense of belonging and culture that so many have missed. Small acts that can be woven, as one would a braid, into each day for new generations of children, something that begins so young it can once again become rooted to the head, and the soul.

For those who look to hair as something to style, not something to honour, it can seem odd to see hair-growing as an act of protest, but for the Anishinaabek, hair is sacred, and for both genders. Journalist, author and former host of CBC’s Up North, Waubgeshig Rice of Wausauksing First Nation explained long hair is symbolic of wiingashk (sweet grass), one of the four sacred traditional medicines.

“In our culture, wiingashk, sweet grass, is the hair of Mother Earth, and it has many medicinal purposes for us. Our hair is similar, and we grow it to sort of emulate that wiingashk. As a result, it is a sacred thing. And it's sort of a private way for us to acknowledge our culture and our spirituality, and also respect them.”

It’s this sacred aspect that makes the hair so special, and only trusted to the hands of loved ones. While Rice’s wife Sarah, or his mother, stepmother, aunts or cousins would be free to care for his hair, no one else would be welcomed. In fact, Rice prefers if it’s one of them.

“My fine motor skills aren’t as good,” he said with a laugh.

But it is an intimate act, the act of braiding someone’s hair, and more so when you consider it as a joining, the way it is for Rice.

“It’s a way of weaving together body, mind and spirit,” he said. “That’s the three essential elements of your being.”

To cut one’s hair is not done lightly, and it is often done in mourning.

“We have beliefs about grief in our culture,” he said. “We believe that your hair carries your emotions; losing a loved one is obviously a monumental experience and your hair sort of absorbs that emotion and that experience, we believe. Part of the grieving process and part of letting go is cutting your hair, so I mean that's something I'm always prepared to do as well.”

A funeral offering for a loved one deeply missed could include the cutting of hair, given as a gift to ensure safe passage for the dead on their journey to the afterlife.

Rice didn’t have long hair as a child. But his younger brother did, and that opened his brother to teasing and ridicule. And even though this was in the 1990s, the bullying and cutting of hair by others continues even now. But as more men embrace their long hair, there is a shift.

Michael Linklater was bullied as a child for his hair, and when his sons also faced the same treatment, he began #boyswithbraids to support them and other boys across the country. Rice himself guest hosted an episode of CBC’s Unreserved on the topic.

Long hair is a subject on Rice’s mind not just because of his crowning glory, but because of his two young sons. While the baby is only three months old, the couple’s four-year-old – whose hair is curly and only now long enough for braiding – loves when his mother braids his hair. While Rice believes his son doesn’t quite understand the finer points of everything his hair symbolizes, “he knows that having long hair is a part of his Anishinaabe culture.” Both his parents have given him the choice about keeping it or cutting it.

For Rice, his decision to grow his came in the combination of two events. First, his father and others in Wausauksing First Nation began to embrace their identity and spirituality, and wanted to pass that to the next generation. The other was moving to Toronto to begin his degree.

“When I got towards the end of high school, you know, I was on my own journey, trying to understand my identity as someone of Anishinaabe heritage and also someone of Canadian heritage.”

In addition to wanting to “fly a flag, for lack of a better term,” to other Indigenous people, it was more about his roots once again.

“When I moved to Toronto for university, I think that's when I really wanted to grow it. For me it was a matter of trying to stay connected; it was a way to represent, in many ways, but also feel a way to stay connected.”

It is that connection he hopes to offer his sons when they are old enough to choose their path as their father and mother did.

Hair can be a fashion statement, a way to frame a face or to express the self. It can also be a way to reclaim a stolen identity, to embrace what was once ripped from your grasp, and to offer your children a link to their past. A braid is a way to join body, mind and spirit, a way to link people and history.

“A braid is an expression of your identity and that unity of everything,” Rice said.

And sometimes “it’s just keeping your hair out of your eyes.”

You can find out more about Waubgeshig Rice and his upcoming work at Waub.ca.