EDITOR’S NOTE: This article originally appeared on The Trillium, a Village Media website devoted exclusively to covering provincial politics at Queen’s Park

TORONTO - In January 2023, Solicitor General Michael Kerzner promised the chiefs of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) that he would let Indigenous police services opt into having the same investigative powers, service standards, governance model and funding mechanisms as non-Indigenous police within a year.

But in the end, it took almost two years.

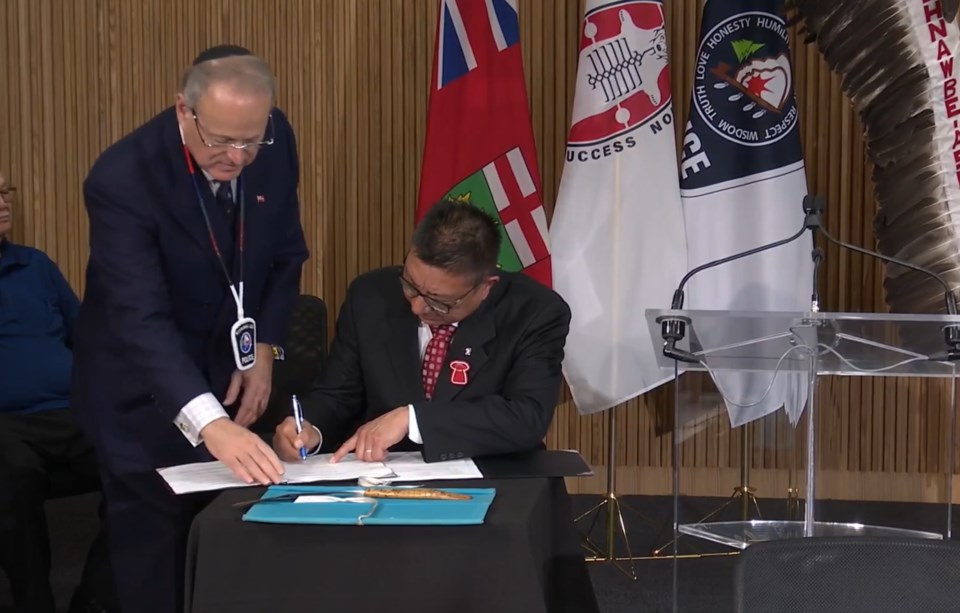

On Tuesday, Kerzner and NAN Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler signed an agreement making the Nishnawbe Aski Nation Police (NAPS) the first-ever Indigenous police force to be recognized under the Community Safety and Policing Act — 30 years after NAPS was created to provide "culturally appropriate" policing services to 34 First Nations across much of Northern Ontario.

Kerzner and NAN leaders hailed the signing as "historic."

"In 2023 I travelled to Thunder Bay to attend my first NAN chiefs meeting. I promised then that our government would meet a very ambitious timeline on the Community Safety and Policing Act. The result of this conversation makes me so proud to be here today because we have done we have done just that," said Kerzner.

"This is the first time ever that a First Nations Police Service has opted into provincial policing legislation."

NAN's deputy grand chief Mike Metatawabin said the agreement means "we are finally accepted and included in the legislation to protect all citizens of Ontario."

"This marks the beginning of our new relationship," he said.

NDP Indigenous and Treaty Relations critic Sol Mamakwa, who was on hand for the signing, also hailed it as an important step forward.

"I just wanted to say congratulations," said Mamakwa while also thanking Kerzner for his work.

This was a moment NAN leaders had been pushing for for decades and is expected to give NAPS the same capabilities as their non-indigenous counterparts.

By opting into the legislation, NAPS will now have to adhere to a set of new standards when it comes to police service and staffing levels, equipment, facilities and governance. Grand Chief Fiddler said such standards are "something that has been missing over the years."

"It will mean that our detachment, for example, will have to meet building code.... That's huge for us," said Fiddler, noting that people have died in NAPS' "makeshift lockups" when the heat went out.

First Nations police services are funded via the federal First Nations and Inuit Policing Program (FNIPP) and have never been declared to be an "essential service." Grand Chief Fiddler said this has led to "severe gaps" in policing in NAN communities.

"As such, they were funded less and they were not backed by the safety or the rule of law," explained Fiddler. "Often NAPS officers have had to work alone."

At the press conference, the solicitor general called on Ottawa to pass legislation declaring First Nations police services as essential.

Plans are now underway to hire 500 more officers for NAPS over the next six years. Kerzner said the government is providing free tuition for NAPS recruits attending the Ontario Police College, the first 15 of whom are graduating on Friday. The province has been covering the costs of the three-month OPC program for all recruits since 2023.

Police board chair Frank McKay also noted that being under provincial legislation will allow NAPS to create specialized units to conduct investigations.

"If there was a homicide, we couldn't do it. We couldn't have a K9 unit. We had to depend on the OPP to provide those specialized services. We were also prohibited from acquiring money to negotiate for our own police services, like legal advice," said McKay.

The province has announced that it will spend $514 million to support NAPS in implementing the necessary changes, but who will fund the police force over the long term appears to be unresolved.

When pressed on who will pick up the increased costs of policing at NAPS, Kerzner didn't commit to the province doing so.

When Kerzner originally met with NAN chiefs in early 2023 he was met with undisguised skepticism that would finally allow NAPS to be recognized under the Community Safety and Policing Act.

At the time, had not yet enacted the portions of the Comprehensive Ontario Police Services Act allowing First Nations to form the police boards necessary to opt-in to the provincial policing system, despite the bill being passed in 2019. It was finally proclaimed on April 1, 2024.

Kerzner and NAN leaders said on Monday that the three-way negotiations between NAN, the province and Ottawa leading up to the signing were very difficult, with funding being the major hurdle.

"The federal government would not easily renegotiate the funding arrangement under the FIPP that they should have done," explained Kerzner.

"That federal program has its shortfalls, which is why Ontario took the significant step — on its own — to ensure our First Nations policing partners have the ability to opt into the legislation."

Metatawabin agreed, saying that "Canada always seemed to be the reluctant participant during the negotiations," while "Ontario was always noticeably open and willing to accommodate throughout the process."

First Nations policing is becoming a more prominent issue at Queen's Park as First Nations push for more control over their internal affairs.

Last week, the Chiefs of Ontario protested at the legislature after launching a lawsuit to force the province to enforce First Nation community laws, something that is optional under the Community Safety and Policing Act.