As the regional moose biologist for the Northwestern Region, I participated in the transition of the moose management program from completely uncontrolled hunting to the “Selective Harvest Program” (1, p. 12), which offered reasonably direct control over the harvest and a promise of an increased moose population.

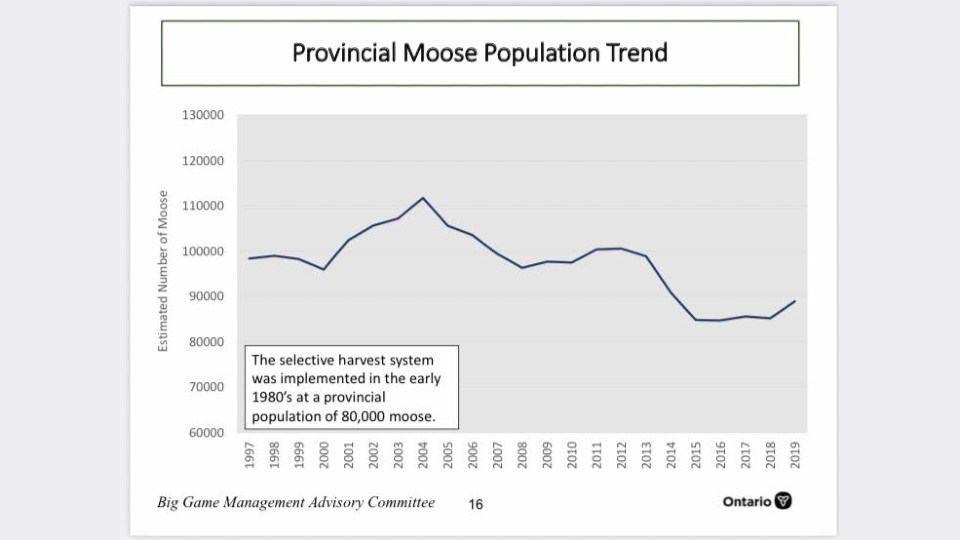

Those controls were never effectively implemented (2) and the promise remains unfulfilled. The population continues to decline, although increasingly intense aerial surveys (2) and “pressure to find moose” (3) implied that it was increasing until 2004 (1, p. 16).

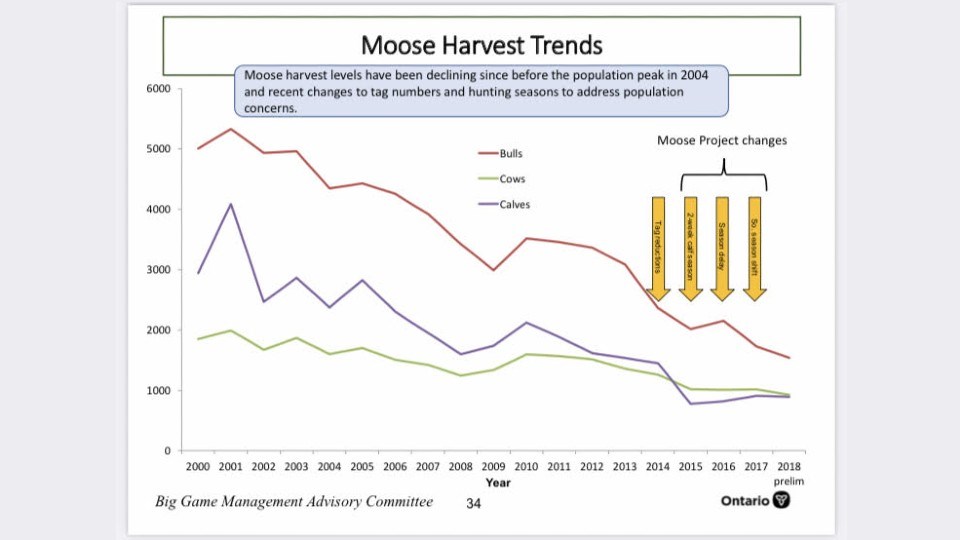

Note that I interpret the decline in harvest (1, p. 34) as additional evidence of population decline rather than a planned response to stop it. If, in fact, it was a planned reduction, then it was obviously ineffective, having failed to result in an increase in the population over nearly 20 years.

The recent changes, mainly season manipulation, have never worked and exhibit both a level of desperation on behalf of MNRF staff to do something without offending hunters and a level of ignorance concerning the history of moose management. Killing cows while protecting calves doesn’t make much sense either, as a provincial practice.

While on the subject of failures, I note that the 2019 review cites “Landscape-scale and ecologically-based population management.” (1, p. 8). I have heard from recently retired biologists that population surveys, while providing estimates at the wildlife management unit (WMU) level are actually stratified, sampled and flown at the landscape level.

Whether these are Cervid Ecological Zones (which, in my opinion, are not appropriate for moose management) or some other large area, I have not determined.

In 2019, 467 hours were flown doing surveys (4, p. 65). This probably means 300 to 350 plots, a far cry from the 1,000 flown annually before my retirement. Apparently they are using computer models to replace real surveys and “creating” population estimates rather than actually sampling them effectively.

I accept, understand and used the advancement and value of technology, but it must be tested and compared with current “best practice”. Since there is not a good correlation between (computer-based) habitat information and moose population densities (12), I don’t believe this testing has been adequately done and as a consequence, such estimates at the unit level are questionable.

MNRF seems to have replaced “evidence-based” (traditional survey) population estimates with “hypothesis-based” (computer-modelled) ones. The point is that if they have not been able to manage effectively at the WMU level with lots of plots, how can they manage at the landscape level with fewer?

One of my observations while with MNR is that when a program is introduced, it is accompanied by public meetings and an abundance of literature to explain the changes. Education declines over time until there is a high degree of misunderstanding and confusion. As an example, I saw nothing in the 2021 Hunting Regulations Summary (4) that explains why calves are harvested. This, over 35 years after the program was started.

I have recently moved to southern Ontario and am amazed at the number of hunters who believe that calves should be given more protection “because they are the future of the herd”. Even the Ontario Wildlands League (5) recommended stopping the calf harvest.

While there might be a simplistic truth to this, game management is far more complex than that. My purpose is to explain some of the complexities.

In other articles, I have suggested what I believe Ontario needs to do to effectively manage hunting and restore the moose population.

My advice is based on general principles, my experience and understanding of the data/information from Ontario and as a provincial strategy. It may not apply everywhere. Local, evidence-based knowledge and adaptive management should dictate what strategy works best in any area.

Game management is based on the principle that there is a “harvestable surplus” if a population is kept below the capability of the habitat to support that population without degrading the environment. That level is called the “carrying capacity” and referred to as “K”. (6)

Below K there is an abundance of food. Animals are healthy and reproduction is high as they try to fill the habitat. At or above K, food becomes scarce, productivity drops and the population may decline. If too far below K, reproduction may be low because animals cannot find each other to mate and factors such as predation may suppress growth. This is referred to as a predator pit (7) and may include human predators as well as wild ones.

The objective of game management is to keep a population at two-thirds to three-quarters of K (6). The number of individuals that can be removed depends on productivity of the species, it’s life history and the extent to which other factors also remove individuals. The relationship between animals being born and those dying dictates whether a population goes up or down.

Moose are polygamous and calves require a significant amount of maternal care during the first year. Calves without a cow have low survival (2, 7). These things do have implications. The other factors, mainly disease, predation, hunter access and hunting by First Nations must also be factored in.

Moose management is very similar to farming cattle (2). You protect your breeding stock, especially the females of polygamous species and harvest mainly the yearlings and “surplus” males. Someone suggested that emphasis on harvesting calves was inappropriate because farmers must cull breeding animals as they get old.

In the wild, wolves do this very effectively.

Since it is difficult to identify yearlings and Ontario moose hunters want big animals rather than calves, the practice has been to plan harvests with 50 per cent (55- to 65 per cent) bulls, 30 per cent (18- to 32 per cent) calves and 20 per cent (10- to 16 per cent) cows (9).

Regrettably, the ministry did not follow adaptive management practices and the herd declined mainly due to overhunting (2, 10). Again, as an example, in 2020 there was a total harvest of 3,293 moose with 1,722 (52 per cent) bulls, 966 (29 per cent) cows and 606 (19 per cent) calves (4, p. 25). While it might have been an acceptable harvest overall (12), it did not match the plan, with cows being harvested at twice the desired rate. Nor did it follow the successful management systems of other jurisdictions (8, 11).

The population is, in my opinion, heading toward a crisis and if the decline isn’t stopped it could create a situation from which it may take decades to recover. If it gets low enough, predation and unregulated hunting could keep it from growing at all, or worse, result in local extinction (7). This eventuality has been predicted, based on evidence, since 1995 yet nothing effective has been done to change it.

Apparently the units around Kenora, once having some of the highest population densities in the province, are almost devoid of moose. I doubt that hunting was the principle cause. Deer numbers had increased many moose deaths, probably a result of brainworm, were being reported about the time I retired.

There were examples of hair loss from winter ticks, although one quick survey on the high density population on the Aulneau Peninsula did not suggest a severe problem. However, all deaths can contribute to a decline.

Closure of the spring bear season would have increased predation on calves when they were most vulnerable and licensing restrictions on wolves didn’t help the situation either. If MNRF had been monitoring these events effectively, they should have adjusted the planned harvest.

Even without data-based evidence of these problems, simply knowing of their occurrence should have resulted in an adjustment of the harvest and enhanced population surveys and studies to determine their magnitude.

There is an adage that if you think you are going to make a mistake, err on the side of conservation. It is better to offer too few tags and protect the population than offer too many and add to the problem.

There are examples from other areas that were in very similar situations to Ontario. Populations were low in Fennoscandia until more direct management was started in the 1970s and 1980s. They resulted in moose harvests increasing from 10,000 in the early 20th century to 200,000 around 2000 (11).

Populations range between 0.2 and two moose/km with some local herds near five to six moose/km. Alaska has achieved densities of more than one moose/km in several units (8) and there have been some units at that density in Ontario (13), so it is possible to replicate their success in North America.

The fundamental principle behind moose management is wise planning with direct and predictable control over the harvest. In Fennoscandia, cows are a small proportion (15 per cent) of the harvest and cannot be shot if they have a calf (14). Calves compose 40 per cent of the harvest with another 15 to 20 per cent being male and female yearlings (11).

Harvest quotas (in Norway) are currently based on 250 ha (618 acres) per moose and the harvest plan is created under municipal authority (equivalent to our Wildlife Management Units) in consultation with landowners (14). Hunter ethics are extremely high and if a moose is wounded, hunting stops until it is found or determined to have been uninjured. If dead, whether edible or not, it is included in the quota (15).

There are differences that preclude exact replication of the Fennoscandian system, but the fundamental principles should be followed.

WMU 48 was probably the best managed unit in the province between 2004 and 2014. It had a citizen’s advisory committee, a dependence on good population information, excellent communications explaining the program, controlled calf harvest, cooperation from the Algonquin First Nation, a good harvest assessment program and a 6-per-cent total planned harvest. The population grew from 625 to 1,200 moose in 12 years. It did achieve this growth with a low calf harvest, but it also had high calf survival (17).

From what I understand, the program started to fail because of staffing changes, pressures internal to MNRF, a shift in planning from local to regional staff, reduced funding and changes in assessment techniques.

Planned harvests moved to eight per cent, then 10 per cent and no longer included First Nations harvest. A population target was set at 1,300 based on “opinion”, because they were not able to do the habitat assessment surveys that would indicate over-browsing.

This is the best example of excellence in management success and failure I have seen. Instead of learning from it, MNRF managers eliminated it, in part because of funding constraints but equally likely because it took a lot of hard work and thinking to establish.

This year MNR changed the harvest control system to almost create the direct and predictable control necessary to rebuild the population (4, p. 56). Unfortunately, there is a lot of sloppiness in the system. For example cow/calf tags (but not bull/calf tags?) are being offered (4, p. 58). Apparently managers recognize that a hunter with a bull tag will not kill a calf. I’m not sure why they think a hunter with a cow tag will.

The concept of killing calves before cows is a very important one (14) because of the low survival of orphaned calves, but it probably won’t happen in Ontario until it is legislated and hunters understand the reason.

Mandatory reporting does not necessarily provide an accurate assessment of the harvest if it is in the interest of hunters to provide false information — like not reporting kills for fear that tags will go down. With the low level of respect hunters have for the MNRF and the misunderstandings regarding the importance of selective harvest and the need for effective control, I think there is ample reason for concern.

The excessive number of tags offered is defeating the principle of truly direct control (2). Although the management system has improved slightly, managers are using the same failed logic regarding “tag filling rates” that prevented the original selective harvest program from succeeding.

To properly emulate the success in Fennoscandia there should be one tag for every moose to be harvested, maybe slightly more in the initial stages of implementation (2). The moose herd cannot possibly achieve it’s potential without this principle being strictly followed.

In order to get the population to respond faster, cows should be given more protection in the form of a smaller portion of the total harvest (see 7 and 10) or a complete prohibition against killing them at all until the herd has started to rebuild. This means reducing the total planned harvest and not switching to a greater harvest of bulls.

Based on a planned harvest of 4 per cent (10) and a population of about 90,000 moose (1, p. 24), an allowed harvest and allocated tags would be close to 3,600 moose. It would be about 15-per-cent less if cows were protected. Under this level of harvest, it is improbable that all hunting parties would get even one tag, even a calf tag, with which to hunt.

I expect this will cause many hunters, especially the more devoted and successful ones to call for closed seasons. They opposed the point system when it was proposed more than 20 years ago (17) because they might not get another tag for many years in some cases.

The point system of tag distribution (4, p 59) should alleviate those concerns regarding unfairness in distributing tags because each hunter will get an opportunity as often as the herd will allow. This, of course, should be a strong incentive for getting the population restored.

The second, and this is truly a personal opinion, is that I expect those complaining the most have had “the best” of this resource and it might be time for them to sit a spell and let others have a turn. This will be an annual reality until the herd recovers enough to permit a larger harvest and possibly one tag (although mostly calves) for everyone — which, interestingly, is essentially the original selective harvest program.

There are other important aspects of game management that are generally secondary to controlling hunting. Little can be done about disease except to study and adjust harvest to accommodate it. Predation may be very important but based on past performance, nobody trusts MNR staff to “manage” wolves in an ecologically balanced way. With their success at managing moose, they just don’t have the credibility or capability.

The harvest by First Nations hunters (18, Item 15), unlike other factors, can and should be included in the management system. Subsistence hunters must become full and active partners in moose management. It is in their own interest that they participate in the process to protect and restore the moose population.

Moose are a significant part of their cultural heritage, an important food source in northern communities and should remain so forever. In addition to traditional values there should be increased economic opportunities for them as well.

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both Internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London, Ontario.

Sources

1: Moose Management Review, 2019. Big Game Management Committee.

2: Moose Management in Ontario: An Alternative Strategy. 2014. A. R. Bisset.

3: Personal communication with an MNR biologist asked to review the aerial inventory program a few years after I retired. Name withheld because I believe he is still with MNRF.

4: Ontario Hunting Regulations

5: Will Ontario’s Moose Sink or Swim, After 2015. Ontario Wildlands League

6: The Harvestable Surplus Concept revisited. 2020. J. F. Organ. Fair Chase

7: Stocastic Predation Exposes Prey to Predator Pits and Local Extinction. 2021. T. J. Clark, J. S. Horne, M. Hebblewhite and A. G. Luis. OIKOS

8: A Comparison of Moose Management between Alaska and Scandinavia. 2011. S. Brainerd and D. James. Sportsman’s Voice

9: Standards and Guidelines for the determination of the allowable moose harvest in Ontario. C. Greenwood, D: Euler and K. Morrison. 1984. MNR internal document.

10: 1999 and 2000 Moose Harvest in Ontario. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Northwest Science and Information Technical Report TR-131

11: Status of the Moose Population and Challenges of Managing Moose in Fennoscandia. 2003. S. Lasvund, T. Nygren and E. J. Solberg.

12: The current recommended harvest is 4 per cent for population growth. Personal communication with Phillip DeWitt, Provincial Wildlife Monitoring Program Leader, MNR

13: MNR internal communications. The Aulneau Peninsula and Algonquin Park have had populations over 1 moose/km.

14: Personal communications with Sven Sletten, forester and moose hunter in Norway.

15: Personal experience while hunting in Norway, 2018.

16: 2014 newsletter from Pembroke district.

17: The Point System: An Alternative to Preference Pooling Within the Resident Draw for Adult Moose Tags. 2003, Alan R. Bisset, John J. Beechie and John M. Barbowski. NWSI Information Report IR-005. This document is not available. Although successfully peer reviewed (a condition for publication), and draft copies printed and provided to OFAH, publication was stopped by Wildlife Section.

18: Big Game Management Advisory Committee report for the Moose Management Review, Ontario.ca.