On July 28, 1943, then United States president Franklin Roosevelt gave a fireside chat to his nation, one of 30 evening radio addresses given by Roosevelt between 1933 and 1944. In this particular one, he addressed the fall of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

Roosevelt vowed that the fallen dictator and “his Fascist gang will be brought to book, and punished for their crimes against humanity…So our terms to Italy are still the same as our terms to Germany and Japan - ‘unconditional surrender.'”

In order to accomplish this goal, the First Quebec Conference, a highly secret military conference, would be held in Quebec City from August 17–24, 1943, by the governments of the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States.

At the conference, the Allies would begin discussions for planning the invasion of France (code-named Operation Overlord) which became the Battle of Normandy, launched 10 months later, on June 6, 1944.

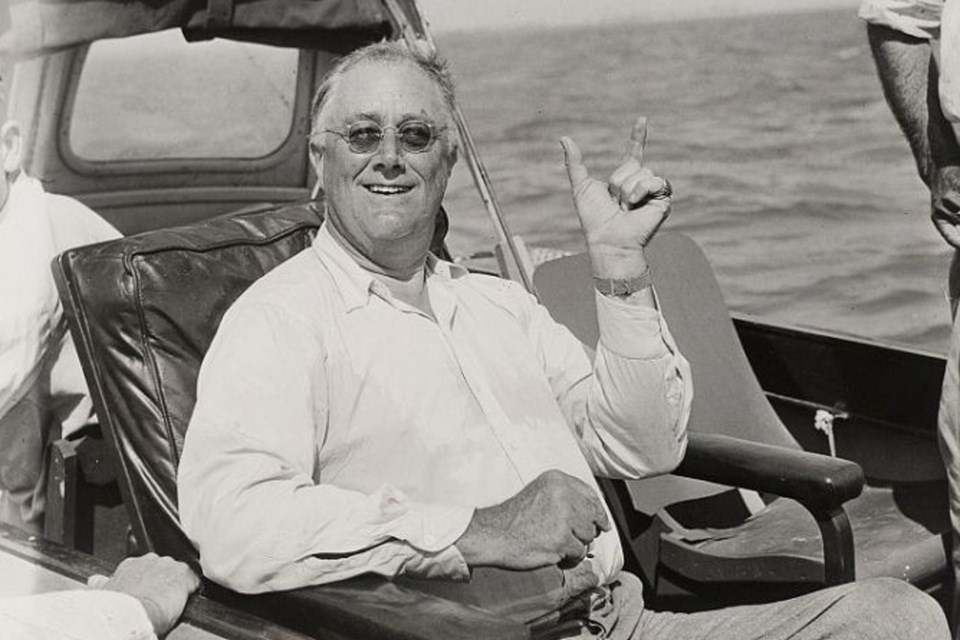

However, for Franklin Delano Roosevelt, something else would come first. For the first seven days of August, Roosevelt would take a little vacation away from Washington and into the hinterland of northeastern Ontario for some fishing and relaxation.

His staff had realized that he desperately needed time off before the crucial decision-making conference. Since Roosevelt loved to fish, a highly secret fishing expedition on Lake Huron was suggested.

Most biographies of Franklin Roosevelt make no mention of the trip. In fact, so much happened during Roosevelt's 12-year presidency that a week-long fishing trip would hardly be worth mentioning.

Late in the evening of July 30, the president's train, which included a 142-ton armoured private car named "Ferdinand Magellan," which the Secret Service had rebuilt following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, left Washington.

Aboard the train were 31 Secret Service agents, nine officers of the US Army Signal Corps, and some of the president's most important wartime advisers. Four RCMP officers joined the presidential party when the train crossed the border. Shortly before daybreak on August 1, the train arrived in Toronto where the original locomotive engine was removed and a Canadian Pacific engine replaced it, pulling the train north.

By midday, the train required another stop, this time at Romford Station (a couple of kilometres west of Coniston). Here, another, larger CP engine was substituted in order to handle the heavy train over the challenging terrain for the remainder of the trip west to Birch Island.

As the train continued on, aircraft flew surveillance over the CPR tracks. Three hours later it arrived at its final destination. From the train’s windows, FDR and his entourage would view a Channel studded with islands and the La Cloche Mountains etching a scenic backdrop.

Local CKSO personality Basil Scully’s father, P.J. Scully, was conductor of the train between Sudbury and Birch Island. His father told him that another security measure which was used involved having another CPR engine precede the presidential train by a distance of nearly one kilometre.

The Secret Service was taking no chances. If foreign agents had somehow gotten word of the president’s trip and had placed explosives on the tracks, the decoy engine would take the hit.

A letter in the files of the Secret Service explains why the presidential party chose the area as the place for Roosevelt's vacation. His visit was recommended by Commander Eugene MacDonald, the President of Zenith Corporation and a summer resident in McGregor Bay.

“…the greatest fresh water fishing I have ever experienced is to be had in McGregor Bay, which is one of the Bays off Georgian Bay on Lake Huron in southern [sic] Ontario....

The fishing for smallmouth black bass and walleye [pickerel] in this Bay is unsurpassed in any other section of the Great Lakes…”

McDonald also explained other advantages, not least of which was that it was relatively secure, as few people lived in the area. Unauthorized persons could not easily get there, which was an important consideration during wartime. There was only one deep-water entrance to the Bay, and it was inaccessible to cars.

Secret Service agents began to arrive on July 28, with RCMP officers shortly thereafter. All of Manitoulin Island and the North Shore were considered a restricted area under wartime censorship.

Upon arrival, the Secret Service contacted local merchants, outfitters and guides, officials of the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railways and Telegraph companies, and Bell Telephone. Carpenters from across the region were hired to construct a wooden platform and a railed gateway that led down to special docks.

The Chief Electrician of the International Nickel Company, and his assistant, were drafted to inspect the train daily. (It’s amazing that a secret involving so many people remained a secret for so long)

Michael Reilly, head of the 31-man Secret Service contingent described the on-site security arrangements to his superior in Washington:

“The president's train is parked on the regular main line at the Birch Island Station area while the two trains a day through the area use the siding for their passage. (At about 500 feet, the main line was closer to the water than was the siding, and the intention was to make it as easy as possible for FDR, a victim of polio, to reach the lake.)

“Switches at both ends of the siding above and below the special train are spiked. In addition to the regular shift of Agents always in the immediate vicinity of the President, we have four uniformed and two plainclothes RCMP men stationed three at each end of the train.“

“Furthermore three armed Naval personnel patrol the woods east of the parked train 24 hours a day and other Naval boats patrol the waters near the Presidential train when the President is not fishing. When the President goes fishing his boat is accompanied by three fully equipped escort boats with eight Agents and three Royal Canadian Mounted Police and thus remain in the immediate vicinity of the President's boat at all times. An air patrol is made of the contemplated fishing area whenever the weather permits.”

With such an entourage, they were required to buy 2,000 worms (for $23.75), from Turner's in Little Current, as bait. At the time, the Manitoulin Expositor remarked that if the president came north yearning for cool nights, his wish had been granted. The temperature fell, and although the train itself was prepared for such a contingency, two cottages which the party had rented were not.

As a consequence, The Sudbury Star pointed out that Turner’s ended up “cleaned out of all woolen blankets on the premises.”

The USS Wilmette, an American naval training ship, was designated to organize the daily fishing jaunts and supply the personnel to accompany the presidential party. The Wilmette’s captain assigned Lt. John Manly to be Roosevelt’s right-hand-man during the trip, and asked him to find a yacht, something “classier than a ship’s boat,” that would be suitable for the President of the United States.

Lieutenant Manly had a friend, Army Lieutenant Ernest Loeb, whose family happened to own a “classy” vessel, the Anna H., upon which they had made several fishing trips together to the North Channel and McGregor Bay.

The Anna H. was requisitioned without the family having any idea what it was to be used for and Manly himself piloted it up through the Straits of Mackinac to meet up with the president’s party. The Charlevoix (Michigan) Courier reported the trip in an article on August 16, 1943, accompanied by a photo of the boat with the headline “Borrowed by President Roosevelt.”

The Ottawa Citizen quoted William “Gus” McGregor, Chief of nearby Whitefish Falls First Nation and one of FDR’s guides on his daily fishing trips. According to Gus McGregor, FDR told him: “You certainly know the fishing holes for these beauties. If I get a few more like this, maybe I’ll have one left when I get back to work to prove to the press boys that I really went on a fishing trip. They won’t believe me without the evidence.”

As for the other guide, just prior to the entourage’s arrival, Ernie St. Pierre was asked by Eugene McDonald if he would like to guide for a very important person, but he didn't tell him who it would be, “we were all sworn to secrecy and told not to contact anybody or to take pictures...” As he wrote in his book, Memoirs of McGregor Bay: “We went to Birch Island and waited. Pretty soon a lot of boats were arriving, boats like I had never seen before....Now cars began to come down the hill letting out men, stationed all along the road with machine guns…Then a jeep came down and drove to the dock near the boat. Commander said, ‘Come on Ernie, I want you to meet the President of the United States.’ It was like I was glued to the dock. Then I recovered and went with him…I shook hands with the President, and then he said, ‘Do you know where we can catch a pickerel or two?’ I said I most certainly did....”

When the first fishing day came, “we started away with all the boats trailing us. Speed boats, cruisers, all heavily armed and then a plane, a Catalina Bomber, made its appearance.”

They started trolling to get the President used to his tackle as he had only fished deep sea fishing before this. He caught two small pike before long. St. Pierre later commented, “With all the boats following behind us, it was like a mother hen and all her chicks behind...And above us the airplanes - just circling all the time, and contacting us through walkie-talkies, asking what kind of fish we caught and how big…The President was having the greatest time.”

St. Pierre found Roosevelt totally congenial and later wrote that when Roosevelt was fishing, surrounded by his advisors, he did not discuss the war.

He concentrated on his fishing, although on one occasion, he did make a facetious remark about rich people who could own expensive vessels: "When I get through taxing those rich bitches in the U.S., they won't be able to afford those great big yachts.”

Sudbury lawyer E.D. Wilkins was fishing in the area when a vessel approached and Roosevelt himself asked, "What luck are you having?" Wilkins had heard rumours of the presidential presence, and he recognized Roosevelt at once. Wilkins held up two bass which he had landed, and Roosevelt, waving back, shouted, "We're going after some like that right away. We had good luck yesterday." After that, the presidential party moved along.

During his time at Birch Island, Roosevelt was officially lost to the world, though an intricate communications network linked his fishing retreat to the White House. For a brief time, the CP Telegraph Office at Little Current became one of the world's principal communications centres at one of the most critical moments in world history.

Over a 14-day span, the presidential entourage sent two dozen telegrams to such destinations as Washington, Detroit, Chicago, and Sudbury. (Roosevelt and Churchill remained in touch with each other several times a day, discussing events in Italy, the forthcoming Quebec conference, and co-operation with General Charles de Gaulle and French forces opposed to Hitler.')

Presidential Assistant William Hassett mentioned the communication network in his diary entry dated July 29, 1943:

Communication headquarters will be set up near Birch Island Station…Arrangements have been made for twice-daily air-mail service; usual telephone and telegraphy connections with the White House will keep the President in close communication with Washington.

The Canadian Pacific Staff Bulletin account of the visit said:

"Every facility was provided to keep the President in touch with his most pressing affairs…A telegraph operator was on duty during the time the train was at Birch Island, and the communications department had two additional first-class operators available at Sudbury on a minute notice if required. Arrangements had also been made to cut in telephone service if this were required."

The other important link in the communication chain that bound FDR to the White House was a float plane which brought the president’s mail and any secret messages. In A Visit From FDR, a manuscript about the presidential visit written in the mid-1980s, Joyce Standish recalled the sinking of the presidential mail plane (she was the only civilian eyewitness to the event). While sunbathing in the backyard of her family cottage off Birch Island, she observed a young man coming up the railway track covered with oil. He blurted out that “the plane was on fire and that his friend, another pilot, was still in the plane.”

Standish raced her small motorboat out to the smoking plane as it slowly sank into the water with the other pilot standing on one of the plane’s pontoons. She urged him to jump, however, he refused. Soon a Navy cutter arrived filled with sailors and secret service agents. “This is a matter for the U.S. Navy to handle,” the sailor on the bow announced, forcing her into a hasty retreat.

She never found out what happened next until the mid-1980s, when she interviewed retired secret service agent Jim Griffith for her book. As Griffith laughed: “A couple of our agents were in the cutter and told us about your yelling those unlady-like swear words…The poor guy couldn’t swim a stroke. He was standing on the pontoon trying to decide whether to hang on and hope the plane wouldn’t blow up or jump and hope he’d get picked up before he drowned.”

A Sudbury Star article reported that the plane engine burst into flames, igniting the canvas exterior, as it was being warmed up and the pilot and gunner aboard at the time escaped without injury. The Navy personnel hurriedly removed any presidential war correspondence and then used an axe to gash slits in the aluminum floats on the plane so it would sink. The Navy planned to salvage the plane, but officials underestimated the depth of the water in the channel (90 feet) and were ultimately unsuccessful.

In 1977, Sudbury businessman Cliff Fielding then spearheaded the mission to recover the plane. The local Aquanauts Diving Club, led by Little Current resident Richard Hammond, found the plane, and began making recovery plans, but gave up the operation when they couldn’t locate many of the plane’s parts.

The remains of the plane rested on the bottom of the bay for 22 more years until June 1999, when Jeff Wallace (grandson of Cliff Fielding) who remembered “hearing all of these incredible stories about the Roosevelt visit and the legend of the lost plane” took a dive team and salvaged some of the aircraft parts.

He obtained permission from the U.S. Airforce Museum to recover the plane. Although the U.S. military would not release the title, they would relinquish all rights to the plane. He also got approval and salvage rights from the Canadian Coast Guard. The aircraft is now permanently installed at the Centennial Museum in Sheguiandah.

The New York Times published a story on August 9 stating that FDR had enjoyed extraordinary luck in his fishing and indicated that he would return to the area to fish again. The story indicated: “Mr. Roosevelt said he ate most of the fish he caught – he loves a real fish fry- and he also had several treats of fresh Manitoulin Island blueberries.” Added Charles R. Bradley, Little Current tug boat captain, attached to the President’s party as official pilot, “Even Fala, the President’s black Scotty, took a liking to our blueberries.”

Former resident David Cork remembers that one evening, his mother took the family dog for a walk near the train. One of the visitors, presumably a Secret Service Agent, yelled: "Grab that dog!" The official apparently had mistaken the Corks' dog for Fala, Roosevelt's dog.

Confusion over the dog convinced Mrs. Cork that the rumours were true, the celebrity had to be Roosevelt.

When asked if the President had done any fishing, his press secretary said that he supposed there was some fishing, but that he had no details.

On the other hand, the Gore Bay Recorder reported that the President had caught five black bass. FDR himself set the record straight when he wrote to his daughter Anna to tell her about his fishing trip. In a letter dated August 10, 1943, FDR wrote:

Dearest Anna:

I have just returned to Washington after a grand six days fishing in the northern waters of Ontario off Georgian Bay. We got a lot of black bass, several walleyed pike and pickerel. I am rested and browned and all ready for the next bout which you will read about by the time you get this…

Affectionately,

Dad

One of Sudbury's leading hardware stores, Cochrane-Dunlop, had heard rumours about an enormous fish which President Roosevelt had caught. As early as August 10, it notified the White House about an annual fishing competition which it sponsored, and they had "taken the liberty of entering the results of the President's piscatorial proclivities in their 1943 fishing contest." The White House thanked Cochrane-Dunlop for its interest but denied that any of the fish were as enormous as had been reported. Therefore, as they had not maintained records, the White House declared ineligibility for any prize.

As an interesting aside, the Secret Service received word from Washington on August 3 that a German POW had escaped from confinement in Gravenhurst. Nobody knew whether he had drowned or where he was headed. In any event, they were instructed to “be more on the alert than usual...Apparently Krug excelled at escapes; on a previous romp he had gone as far as Texas before being apprehended.”

Clad in nothing more than a bathing suit at the time of his unauthorized departure, he headed to North Bay. There a policeman recognized and arrested him as he waited on the platform outside the CPR station. There is no evidence, however, that he knew of the presidential visit or had any plans to head to Birch Island.

On the last day, Roosevelt autographed a postcard for his main guide Ernie St. Pierre, the President wrote: "To Ernie on a perfect day, Franklin Delano Roosevelt."

When it was time to return to Washington, the train left McGregor Bay late in the evening of August 7, stopping again briefly at Romford Station before continuing on and reaching Washington the following morning. A stone memorial marking the occasion was installed in 1946 on Highway 6 at Birch Island, not far from where Roosevelt's special train was parked during his visit.

Jason Marcon is a writer and history enthusiast in Greater Sudbury. He runs the Coniston Historical Group and the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page. Then & Now is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.