This weekend the city of Timmins will play host to Hometown Hockey, a nationally televised celebration of the game's roots in Canadian communities, big and small.

Big crowds are expected for the weekend's activities, and many are expected to pass through the Timmins Sports Heritage Hall of Fame at the McIntyre Arena.

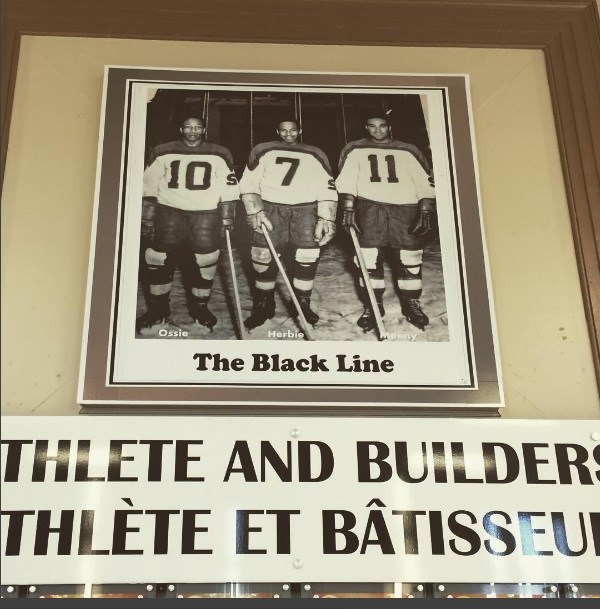

Perhaps one of the most significant photos in the building is simply titled 'The Black Line'. It shows three players - 'Ossie', 'Herbie', and 'Manny'. Three men who in 1941 are widely believed to have been the first all-black line in hockey, outside of the Maritimes' 'Coloured Hockey League' which ran from 1895 to 1930.

The man in the middle of the photo, and by far the most well known in hockey circles, is the great Herb Carnegie - a man who was once described as the best player in hockey outside of the NHL. Born in Toronto to Jamaican immigrants, he fell in love with the game at an early age playing on frozen ponds and listening to the legendary voice of Foster Hewitt. He made his way to Timmins with a bit of encouragement from his brother.

"My uncle Ossie went up north to play hockey, my father was still in school. He encouraged my father to come up there, because their love was hockey, and yes they did work in the mines. So my father left school, and I don't think he finished his grade 12 year, but ended up going to play hockey with his brother," said Bernice Carnegie, Herb's daughter and a notable life enrichment speaker.

The Carnegie brothers played for the Buffalo-Ankerite Bisons of the Northern Ontario Senior League, dazzling crowds and making headlines, when Vincent 'Manny' McIntyre, a player from Frederiction, New Brunswick heard about them.

"He was the one that orchestrated the three of them getting together, because back then they didn't have agents to promote them. Manny ended up promoting himself into the lineup, my uncle and father had never heard of him before," said Bernice.

In Herb Carnegie's 1997 autobiography 'A Fly in a Pail of Milk', he described seeing McIntyre on the ice for the first time.

"He kind of said 'Hot dog, he can really skate!' and thought he'd be a terrific addition to the team. Their manager at the time, saw the benefit of putting them together because of course they were an anomaly in that time," she said.

"It turned out to be hockey history really, that they ended up playing together and were very well known in terms of fans coming from miles around to actually see them play, because they were so different."

Racism, both casual and direct, was very prominent at the time. The headlines reflected that.

"A lot of titles that permeated the papers back then had titles like 'The Brown Bombers' and 'The Dark Destroyers' and 'The Dusky Raiders' and so on," she said.

The Black Line only played one full season in the Timmins area (1941-42), but were reunited in the Quebec Senior League in the 1945-46 season for the Sherbrooke Randies. A league they dominated for several years.

Herb Carnegie was unquestionably good enough to play in the NHL, before he even came to Timmins, but was denied the opportunity by Toronto Maple Leafs founder and owner Conn Smythe, the man whose name graces the NHL's most valuable playoff performer trophy.

"I would take Carnegie tomorrow, for the Maple Leafs, if someone could turn him white," recalled Herb Carnegie about Smythe's alleged statement, in an emotional 2009 interview with Hockey Night in Canada's Elliotte Friedman. He was 18-years-old, and a star in junior for the Toronto Young Rangers. The statement haunted him for the rest of his life.

Willie O'Ree broke the NHL's colour barrier on January 18, 1958, becoming the league's first ever black player, suiting up for the Boston Bruins in a game against the Montreal Canadiens. O'Ree gave much of the credit to pioneers like the Carnegie brothers. It was a great step forward for equality, but one that should have happened many years earlier. Herb never got the chance to play in the big leagues.

"We'll never know what he would have been capable of. Although he went on to have an amazing life, that always 'stuck in his craw' so to speak, to know he never got to compete with the best, on the same playing field. He had to live with that for the rest of his life, as many times he was told he was good enough," said Bernice.

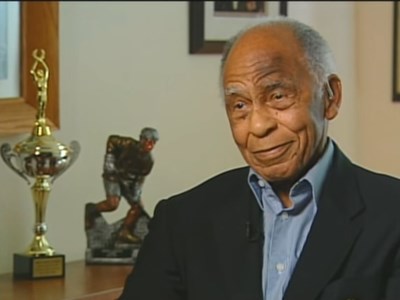

Herb Carnegie in a 2009 interview with Hockey Night in Canada when he was 88 years old.

Herb Carnegie in a 2009 interview with Hockey Night in Canada when he was 88 years old.Herb went on to become a star with the Quebec Aces, where he played alongside a young Jean Beliveau, a man who he shared a lifelong friendship with, and went on to become a true legend of the game. According to Beliveau, he learned much from Carnegie.

After Herb finished his playing career with the Owen Sound Mercurys in 1954, he opened Canada's first registered hockey school in North York, Future Aces, a program that is still thriving today.

Bernice said her father's greatest sporting feats may have come on the links instead of the ice. Herb Carnegie won two Canadian men's senior amateur golfing championships (1977, 1978) along with 22 other golf championships. Despite being very talented, he couldn't work on his game while he lived in the north.

"When he tried to join a club up there in Timmins, guess what? They sent his cheque back with no explanation. They denied him the opportunity to play on that course. That's what it was like back then. Actually, they wouldn't even allow them to live in the city. He had to live outside of the city limits, in South Porcupine."

Manny McIntyre lived in the Timmins area for just one year. Ossie from 1939 to 1944, and Herb from 1941 to 1944. All three of them were inducted into the Timmins Sports Heritage Hall of Fame in 2014. Herb Carnegie was inducted in Canada's Sports Hall of Fame in 2001. He passed away in March of 2012 at the age of 92.

In 1993, the NHL formed a Diversity Task Force and appointed Willie O'Ree as its Director of Youth Development. Since O'Ree's debut in 1958, dozens of black and bi-racial players have played in the NHL.