When Thomas To and his wife bought their home in 2009 in East Gwillimbury, less than an hour north of Toronto where they had been living, the property was obviously special. Compared to big-city prices, the location was affordable, offered lush forest to roam, plenty of wildlife, and even fishing right out their door. “It’s 24 acres backing onto the Holland River, a wooded lot, nice and natural,” says To, standing in his sprawling yard one morning in late April.

Since purchasing the land, the family has grown to include two dogs and two children: a son, 9, and a six-year-old daughter. But another big change is looming—one far less idyllic: the Bradford Bypass, a debated-for-decades highway now threatening to cut through To’s piece of paradise.

Walking along the middle of his property wearing tall rubber boots, To nods at a tree toppled over. “That is Mother Nature’s way of saying ‘no’ to the Bradford Bypass,” he says, and it’s hard to tell if he is joking. Soaring trees on either side are dotted with orange, pink and purple plastic ties, which To believes are markers for the future highway. An area near the river’s edge has been clear-cut and subject to an archaeological dig to determine whether the land is of historic or Indigenous significance.

As he heads to a muddy path leading to the river, To pulls out his cell phone to look at an aerial photograph featured on the official website for the Bradford Bypass. He points to his lot, a portion of which falls within the highlighted “proposed right of way.”

To’s land is not the only one in the crosshairs. This northern stretch of Yonge Street in York Region is lined with dozens of family homes on big yards with play structures interspersed with farmers’ fields. Many front lawns display red and white signs: “Stop the Bradford Bypass.” It was one of the neighbours who first told To that plans were in motion once again to finally start building the freeway. His first reaction was a common one around here. “Why?” To recalls saying. “Why bring it back now?”

With the Ontario election just days away, that question has never been more urgent. The future of the Bradford Bypass (and the 413, another controversial highway) was front and centre during the recent televised leaders debate, and candidates across York Region and Simcoe County are being asked the same thing on the campaign trail: Where do you stand on the bypass?

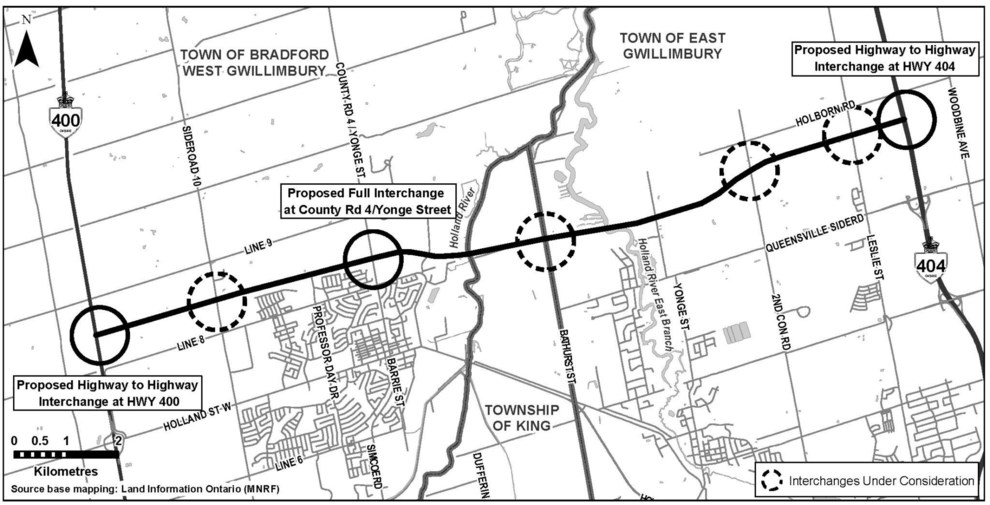

For those who don’t live in these parts, where the discussion has dragged on for nearly half a century, the Bradford Bypass is a proposed east-west highway—16.2 km, four lanes, up to seven interchanges—that will connect two of the province’s busiest north-south arteries: Highways 400 and 404. On a map, the would-be road resembles the rung of a ladder, connecting one leg to the other.

It’s one of those touchy subjects like COVID, politics and religion that you just don’t talk to people about because nobody’s indifferent.

Those in favour of the bypass—chief among them Doug Ford, who has championed its construction since becoming Ontario premier—view the highway as a long-overdue project that will help “unlock the full economic potential” of the province: easing congestion, slashing commute times, creating jobs, and paving the way for ever-increasing population growth. Maybe most importantly, proponents say the bypass will divert traffic away from smaller roads, including the main street in downtown Bradford that’s often jammed with cars and trucks bound for the 400.

But for those who oppose the bypass, the plan is catastrophic. It would cut through a portion of the Holland Marsh—the largest and most significant wetland in the Lake Simcoe watershed—and threaten wildlife habitat as well as culturally and historically important shorelines. What’s more, critics say the Ford government has dodged scrutiny on the project by relying on an environmental assessment that is nearly a quarter-century old.

If re-elected, Ford promises to move full speed ahead; during a visit to Bradford last November, he called the bypass “a no-brainer” and took aim at “ideological activists who oppose any and all highways over hardworking families.” NDP leader Andrea Horwath is vowing to scrap the project, while Liberal leader Steven Del Duca says he will order an updated environmental assessment before committing to a decision.

In so many ways, the epic saga of the Bradford Bypass is relevant to towns and cities across Ontario that are struggling to reconcile the same conflicting interests: population growth, suburban sprawl, public transit, affordable housing, downtown revitalization, greenspace protection, and of course, the climate crisis that is already underway. Indeed, the way forward is anything but straightforward. If it were, the bypass would have been built long ago—or abandoned altogether.

“We lose the discussion when we present it as binary,” says Jonathan Scott, a young, first-term Bradford councillor who studied law, and is now leading downtown revitalization efforts. In other words, no one likes being stuck in traffic for hours, and people on all sides concede that new roads are required, and environmental concerns must be addressed. “A highway,” Scott says, “is not a neutral proposition.”

Amid all the debate, one thing is certain: Every person who has an opinion about the bypass—families, farmers, small business owners, commuters, politicians, urbanists and environmentalists—wants the same thing: what is best for their community now and for future generations. And as Scott puts it: “No one is wrong.”

Which is precisely why the project has been diverted so many times over the years. In effect, the Bradford Bypass is a road that leads to many places.

“My father was in construction when they were paving way back when, so they’ve been talking about this since 1968 or maybe even before that,” says Peter Dykie, a longtime town councillor in Bradford West Gwillimbury, who was first elected in 1985. A small business owner, Dykie operates a jewellery store on the main street in downtown Bradford, so he sees firsthand why so many people in this town of 43,000 are in favour of the bypass: Holland Street East has become a de facto thoroughfare for commuters and transports, to the detriment of local shops and their customers.

“A lot of people don’t feel safe, you’re walking on the sidewalk and then all these big trucks zoom by,” he says. “If you go look out my store right now there’s about 25 cars in line at the lights.” All those idling engines, Dykie notes, cause pollution, and when they’re moving “everybody’s rushing.” One Friday a few years ago, Dykie was hit while crossing the street after work. “I rolled off the truck and landed,” he recalls. “I couldn’t believe this happened to me.”

Down the street, Lorraine Schmidt has just opened Hidden Beauty Vintage, a furniture restoration store inside an historic Victorian home that also sells cards, art and home decor made by local artists and female entrepreneurs. Her view on the bypass? “It can’t come soon enough,” she says. As a longtime resident of Bradford, Schmidt already knew traffic was bad, but seeing it all day has been a shock. “I couldn’t believe the speeders and transport trucks coming through like it’s ‘Mario Speedrun.’ ”

Given such trouble, it’s no surprise the promise of transportation solutions in the ever-expanding Greater Golden Horseshoe has been an enticing ploy for both Liberal and Conservative governments, which have alternated over the years between pushing and tabling the Bradford Bypass. The latest budget includes $2.6 billion in funding for highways, all part of a campaign to leverage commuter angst and an appetite for improved infrastructure among Ontarians. At the same time, the Ford government has been busy issuing Minister’s Zoning Orders (MZOs), which override local planning authorities to allow the province to approve developments without public input or any chance of appeal. Over the last few years, at least 18 MZOs were approved for land previously designated for agricultural or heritage protection, a stat that has been heavily criticized.

Gord Miller, who served as Ontario’s Environmental Commissioner from 2000 to 2015, says the Ford government is “emboldened and the Bradford Bypass situation is the culmination of all that stuff they’ve gotten away with—and now they just don’t seem to care.” He cites the fact that the government exempted the bypass from a provincial environmental impact assessment, which would have closely examined the highway’s potential effects on the wildlife and watershed of the Greenbelt and Lake Simcoe. The only such assessment began in 1997 and was completed in 2002.

Miller questions how plans are being made, and to what extent the concerns of climate activists and rural residents are being considered. “These kinds of decisions have to be consulted meaningfully, intelligently,” says Miller, who now chairs Earthroots, a conservation organization. “They don’t have to win or get their way,” he says, referring to those who oppose the bypass. “But it’s widely recognized that [public consultation] is important and beneficial.”

To that end, a group of seven environmental and community organizations asked the Trudeau government to conduct its own federal impact assessment on the Bradford Bypass. Twice requested, twice rejected. Now the group, represented by Ecojustice, has launched a lawsuit against Steven Guilbeault, the federal minister of environment and climate change. They argue Guilbeault did not base his decision on current evidence and “interpreted his power very narrowly,” says lawyer Ian Miron. Bigger picture, his clients are concerned that what is happening “will set a precedent that will weaken the entire designation scheme” for future environmental impact assessments.

Even without a new assessment, environmental concerns are abundant. Critics say the Bradford Bypass will cross 27 waterways and sensitive wetlands in the Holland Marsh, a Greenbelt region nicknamed “Ontario’s vegetable patch” because of its fertile soil. All told, critics worry the highway would impact approximately 11 hectares of wetland and 39 hectares of wildlife habitat, including areas that are home to species such as snapping turtles, chorus frogs and red-headed woodpeckers. However, the Ford government is quick to point out that the Holland Marsh contains more than 3,000 hectares of wetland area—and that the bypass will cross only 10.75 of those hectares, or 0.35 per cent.

Critics of the bypass also worry about road salt runoff during the winter. If built, the highway is expected to average more than 30,000 vehicles per day, potentially contaminating groundwater and further polluting Lake Simcoe. There are also concerns about greenhouse gas emissions, as well as the health of migratory birds and fisheries. And there is research showing that highways actually attract more traffic—a concept called “induced demand”—rather than alleviate congestion.

“People who commute like to live near highways,” says Bill Foster, who 29 years ago founded Forbid Roads Over Green Spaces (FROGS), one of the groups now suing the feds. He believes that if the highway proceeds as planned, the problems ahead will extend far beyond increased traffic, noise and pollution to “a whole pile of sprawl.” His organization has recommended a series of regional roads rather than the bypass. “You’ve got developers who have bought up all the property around here just rubbing their hands,” he says. “And the problem with that is we can’t service it.”

At this point, after decades of fighting, Foster is at least hoping for a compromise. “The best case scenario would be—how do I put it? A negotiated settlement,” he says. Even though he believes the case against the minister is strong, Foster says “it’s really in no one’s best interest to battle this out in front of a judge.”

What’s at stake is not only legal, it’s personal. Foster’s house, which he built himself, is just up the dirt road from Thomas To in East Gwillimbury. And like his neighbour, a portion of Foster’s 30-acre property falls within the province’s “proposed right of way.”

If you ask Foster where he lives, his one-word answer says it all: “Heaven.”

Whatever high-level political and judicial drama is unfolding, it is the local residents who best express the depths of the bypass debate. On the main street in Bradford, a block away from Dykie’s jewellery store, Heather Williamson runs The Flower Merchant, where people come from near and far to buy her floral creations. There is so much downtown traffic that Williamson doesn’t keep the doors or windows open, even in good weather, because everything winds up covered in black exhaust dust. Most of her customers use the back door to avoid Holland Street East altogether.

The bypass, at least in theory, would reroute heavy traffic away from downtown Bradford—and not soon enough, if the population projections are accurate. The town is already one of the fastest growing communities in Ontario, and is preparing for the population to surpass 50,500 by 2031. By 2051, the number of people living in Simcoe County (excluding Barrie and Orillia) is expected to balloon to 550,000 from the current count of approximately 357,000. Throw in the fact that York Region is expected to be home to 1.79 million people by 2041—and that the number of transport trucks in Ontario is expected to double over the next three decades—and it’s easy to see why many commuters and corporations support the construction of this highway.

But for Williamson, there’s a catch. While her flower shop is located in Bradford’s core, her family lives in a more rural area between Lines 8 and 9, where the bypass would be built. Williamson suspects the bypass “may affect our home more than our business” because of the construction, as well as future noise and pollution. She is, literally and figuratively, caught in the middle of the controversy—with the interests of her small business and Bradford’s downtown viability on the one hand, and the joys of country living on the other.

Considering this, Williamson is careful in her comments about the bypass. “It’s one of those touchy subjects like COVID, politics and religion that you just don’t talk to people about because nobody’s indifferent.”

Just ask Bessie Ditta and Joe Di Feo. As BradfordToday.ca recently reported, the couple had their income property in Bradford West Gwillimbury “ripped out of their hands” by the province to make way for the bypass, the fifth property expropriated so far by the Ministry of Transportation. The couple said they feel “violated,” especially because they don’t believe the government offered fair market value for their land. But like so many locals, they don’t actually disagree with the bypass—even after losing their property because of it.

“I do believe we do need a highway,” Ditta told Natasha Philpott, editor of BradfordToday. “I am not disagreeing with that. There is a lot of congestion in Bradford ... However, timing should have been of the essence, putting a lot of people first before just throwing people away, out of their homes.”

More care and compromise, it seems, would go a long way. Councillor Scott considers himself an environmentalist and an urbanist, and sees no contradiction. In fact, Scott believes it’s this kind of blended thinking that will most benefit the bypass project and the downtown revitalization of Bradford. In general, “the entire principle of sustainable development is that if you do something that isn’t neutral or is negative, you will have offsetting programs,” he says. “That doesn’t mean you don’t proceed. It means you mitigate and compensate.”

Such thinking is already underway in Bradford no matter what happens with the bypass. Scott says there’s been a push for a phosphorus recycling plant and federal funding to reinstate a program that helps protect the watershed. On the issue of road salt runoff, Scott says “that’s not the highway’s fault, that’s the fault of our current standards for dealing with ice and snow.” Bradford has stepped up its use of gravel and dirt. Scott also insists that “growth doesn’t have to be sprawl,” pointing to Bradford’s attempts to densify its core. Three condos have been approved to go up downtown with a fourth in process, and there are plans to redirect some street parking off the main road to nearby lots, claiming that space for wider sidewalks, patios and planting.

Standing in a freshly paved parking lot out back from Holland Street East—where the rumble of traffic makes conversation almost impossible—Scott points to the quaint wooden addition at the rear of Williamson’s flower shop: gazebo-like, with reclaimed and stained glass windows strung with little lights. It helped with curbside pickup over the last couple of years, Scott says, and created a welcoming alternate entrance for customers.

Inside, Williamson wonders what many around here do: Will the bypass actually go through this time? “I don’t believe it until I see it,” she says. Equally unclear is the impact if it does. “I’d like to say it’s going to be awesome,” she says. “But we don’t know.”

Twenty minutes away in East Gwillimbury, Thomas To has a lot of unanswered questions, too. He’d like to tackle some renovations, but doesn’t feel comfortable proceeding while his trees are being tagged. If the family winds up expropriated, To worries he’ll never find another place as special as this one.

Standing in the rain at the top of his long gravel driveway, To’s electric sedan is plugged into a charging station at the side of the house. A hybrid SUV sits beside it. Asked if he considers himself an environmentalist, To shrugs. “Not really,” he says. Waving at the vehicles, he adds: “Oh these? They save me money on gas.”

He may be more of a pragmatist, but the significance of what’s at stake is not lost on To. During the pandemic, his family spent more time at home working, studying and playing on their land than commuting, and they were grateful for so much space to enjoy. These days, To is relying on both pragmatism and optimism as the family waits to see what will happen with the bypass. The plan for now, he says, is to “live life to the fullest.”

Where they are, while they can.

A veteran journalist, Cathy Gulli spent 11 years as a staff writer at Maclean's. Nominated for six National Magazine Awards, her writing has also appeared in The Globe and Mail and National Post.