TIMMINS - As we approach Remembrance Day, we should take the time to understand the roles many of our citizens played during the Second World War. From soldiers to volunteers, everyone was somehow involved in the war effort; stories of heroism, sacrifice and tragedy abound. Here are a few of our local stories.

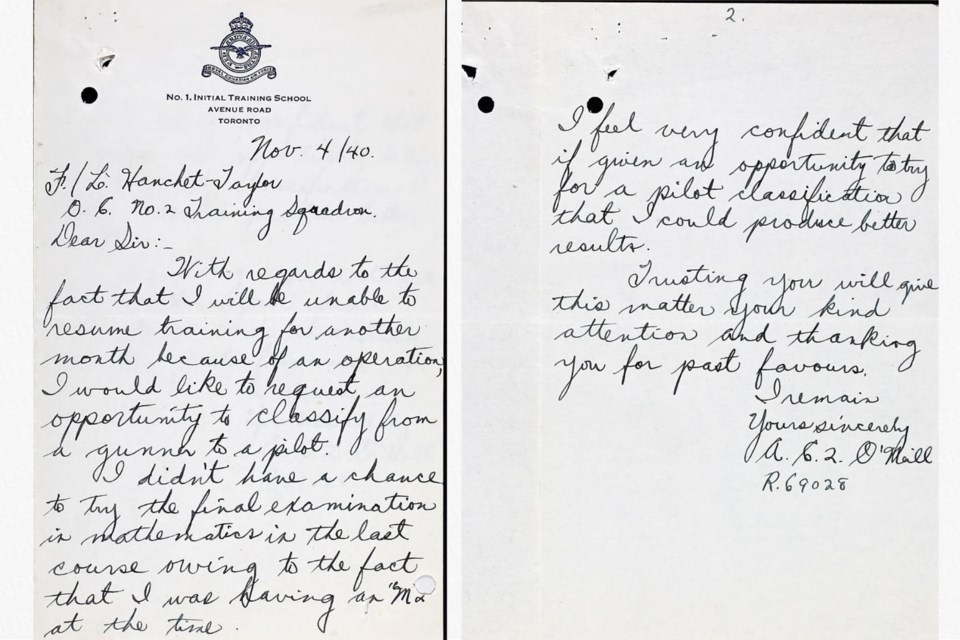

Sgt. Pilot Bernarr (Bernard) Peter O’Neill, the first airman from Timmins to receive his wings in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), was reported as missing in action after being on a bombing flight “somewhere in Europe”.

He was a miner at the Buffalo Ankerite gold mine when he enlisted. Sgt. Pilot O’Neill graduated in May 1941 at Uplands, the RCAF training grounds in Ottawa. He was transferred overseas soon after his graduation and took part in a number of raids over Europe. While some people tend to romanticize the life of an RCAF pilot during the war, the job was anything but easy. According to the Royal Air Force website, “Wartime flying, piloting a 350 mph fighter daily to within an inch of your life, was in fact a deadly serious business requiring a cool head and a steady, calculating nerve. Only a fool would treat it casually as, if he did, he would soon be bounced by an Me 109 and become another name on a war memorial.” It was estimated that the lifespan of aircrews during the Battle of Britain was an optimistic four weeks. Many of the men had clocked in about one hour of flying time in their fighter planes before being sent on a run. Sgt. Pilot O’Neill, son of Joseph and Isabelle O’Neill was one of 17,397 RCAF airmen who lost their lives in the Second World War. He was just 24 years of age when he died on Jan. 2, 1942.

Not everyone served overseas — some members of the Algonquin Regiment were entrusted with guarding power plants in southern Ontario, playing a vital part in the Canadian war effort. Private Omer Côté visited his parents who lived at 71 Mountjoy St. S., while on leave during the 1941 Christmas season. He was very proud to have been a member of the 14th Brigade as the troops were tasked with guarding the huge hydro-electric stations at both Niagara Falls and Allensburg. The assignments lasted six weeks and then the brigades were rotated out and placed elsewhere on similar duty.

Recruitment efforts were a going concern in the Porcupine in the early days of 1942. The local papers reported regularly on how many men signed up each week. Sgt. Melville who was temporarily in charge of recruitment in the district stressed that a large number of armament artificers were needed for the various branches of the service to work with anti-aircraft equipment, motor vehicles, field instruments and wireless (radio). Armorers were in great demand as well as tradesmen, which included blacksmiths, carpenters, drive mechanics, electricians, fitters, hammermen and machinists. Clerks and cooks as well as shoemakers and watchmakers were also in demand. Monster recruitment rallies like the one held at the Palace Theatre on Jan. 25, 1942, under the auspices of the Mine and Mill Workers’ Union (“Canada Needs Fighting Men- Miners Will Fill the Need!”), worked to meet the demand.

And it wasn’t only personnel that was needed for the war — cold, hard cash was also in demand. The Porcupine was well placed to help fundraise; the Victory Loan objective for 1942 for the Cochrane District was set at $1.75 million. The entire province of Ontario was asked to raise $403.9 million — a staggering amount for the time, when you think about it. The Porcupine’s share came in at $1.1 million, the balance to be raised by Kapuskasing, Iroquois Falls, Cochrane, Smooth Rock Falls, Hearst, Matheson and Monteith, Ramore and Holtyre and a group known as “special names”. The local Victory Loan committee was charged with getting the word out and making sure that people participated. Pageants, a visit by the army train and a visit by a group of Norwegian airmen were all events organized to help the effort. By March 19, a mere six weeks into the campaign, the people of Cochrane District raised a whopping $2.1 million with every community showing an increase in their donations from the last year. Hearst was the champ, coming in at 240 per cent over its quota.

Finally, the local mines were pressed into service at the end of March 1942. The Wartime Mine Shop Association was officially formed in June 1941 to undertake war work in machine shops, similar to the “bits and pieces” programmes run in England and Australia. The mines of the Porcupine were ahead of the game as they did not wait for the national organization to take root; they had started work in early 1941. Fourteen mines in the Porcupine were engaged in war work. All were running 24/7, had engaged more staff and were training many men who were new to the mining business. The majority of the work in our mines was part of the cargo shipbuilding programme – every large ship built in Canada had some part in the engine room built in the Porcupine.