The history of the Porcupine Camp is filled with colourful characters. There are many legendary tales from the region’s pioneer era.

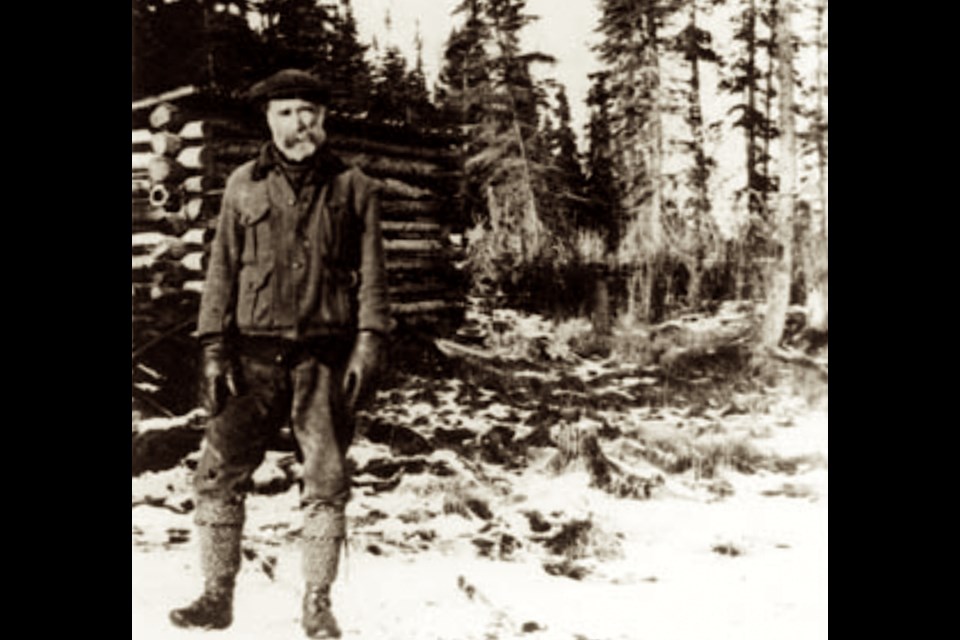

One of the most charismatic figures was Sandy McIntyre. He was a successful prospector who enjoyed life in the bush and, when finances permitted, having a good time.

McIntyre is credited with two major gold discoveries, the McIntyre Mine in the Porcupine Camp and the Teck Hughes Mine in Kirkland Lake. After two rich finds, many would expect the protagonist of this tale to retire rich and join the upper crust of society. That just wasn’t McIntyre’s style.

The legendary prospector enjoyed life in the moment.

He was born Alexander Oliphant in Scotland, immigrating to Canada in 1903. He was so unhappy with his life in Scotland, he left his wife behind to come to a new world. Along with a new life came the new name Sandy McIntyre. He used his mother’s maiden name, McIntyre, and his nickname, Sandy.

A story in the April 2, 1936, edition of The Porcupine Advance, detailed his early years as a new Canadian, straight from the prospector’s mouth.

“Old-time Northern prospectors in their hundreds are acquainted with Sandy and his history,” the story read. “A patternmaker by original trade, he came to Canada from Scotland in 1903 in search of fortune and adventure and he has had much of both. One of his first jobs in this country was ‘tagging along with a bunch headed for Haileybury,’ here he secured a job with a company then in competition with the Hudson’s Bay Company.

“He travelled north, transporting supplies into the territory northeast of Abitibi and, incidentally, being seriously inoculated with the prospecting virus.”

McIntyre maintained it was rugged bushmen like himself that paved the way for early development in the North.

“It was the greenhorn prospectors who developed it,’” he says in the article. “Although an amateur in geology, Sandy found copper for his first strike and rapidly sold to a Cleveland firm for enough to encourage a continuance, plus plenty for a real grubstake.”

He later met Dr. W.L. Goodwin, who instructed one of the first mining schools in Canada.

“I was his Man Friday and in return he taught me something about rocks,” he said. “Then I really got interested and although Doc went back to Ottawa I kept on prospecting, sure I would strike it big and become rich.”

Word spread of a boom at Larder Lake. McIntyre went there in 1906.

“They were actually staking claims there in the water and I saw more hundred-dollar bills changing hands there than I’ve seen nickels in circulation during the past few years,” he said.

The Larder Lake rush faded, but not until thousands had been spent on development.

Three years later, there was a rush in the Gowganda area. McIntyre staked nine claims and sold them to a Toronto syndicate for $10,000. Those nine properties never worked to a profit and soon faded out.

A few years later, McIntyre hit the big time. He met up with German immigrant Hans Buttner. The duo traced the steps of Benny Hollinger and Jack Wilson, who had previously struck it rich with huge gold finds. The two crossed a small lake and staked claims after finding evidence of gold along the shore and further inland.

Those claims later became the site of the McIntyre Gold Mine.

Buttner took his share of the proceeds and returned home. But how much McIntyre actually profited from the discovery changes from story to story.

“Sandy bobbed up again in the forefront of the Porcupine gold rush,” the 1936 story in The Advance read. “Sandy is accredited with uncovering freak deposits of fabulous richness. The McIntyre Mine was first registered in Sandy’s name and it is claimed that he sold out for $125,000 in cash.”

A story about the death of McIntyre tells a different story. A front-page article in the July 8, 1943, edition of The Advance was headlined “Sandy McIntyre Dies in Christie Street Hospital at Age of 74.”

The story said the claims were bought for considerably less. “This property was sold by the staker for a few hundred dollars but today is literally worth millions.”

Another story puts the dollar figure somewhere in between the two previously mentioned figures.

R.J. Ennis, general manager of the McIntyre Mine, was the keynote speaker at a dinner meeting for 100 at the Empire Hotel for the Porcupine branch of the Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. Details were provided in the June 15, 1936 edition of The Advance.

“It all began when Sandy McIntyre came in from Porcupine Lake and staked two claims adjoining the Hollinger in the summer of 1909,” the story said. “One of the claims, No. 1307, extended into the Hollinger’s already explored rich vein system like a piece out of a pie. In the end, this claim accounted for a large proportion of the McIntyre’s production below the 1,000-foot horizon.

“Sandy found some free gold in the southwest corner of the claim but on the whole the show was not encouraging. Bartering small interests in his claims about the country, Sandy finally realized about $15,000. ‘He’s getting along pretty well in years now but still prospects and is assured of a grub stake because his name is the first one on the monthly payroll,’ Ennis said. ‘His occupation is put down as sampler on the lowest and newest level.’”

Regardless of the actual amount earned from the sale, his claims spawned a gold mine in his name. And McIntyre enjoyed life as a prospector — when the party fund ran dry.

A story from the Republic of Mining in 2008 provided details of his next big find.

McIntyre was hired to prospect claims in the Kirkland Lake camp, owned by Jim Hughes, one of the owners of the McIntyre Mine. There, McIntyre located several rich veins. His reward was 150,000 shares and a cash bonus. Teck Hughes mine closed in 1968, produced 3.7 million ounces of gold.

McIntyre reportedly sold his shares while partying in Montreal for $450. Shares eventually peaked at $10 each. Teck-Hughes Gold Mines Ltd formed in 1913 to develop the mine, which was open until 1968.

He continued prospecting in the North. As times changed, McIntyre didn’t. In the summer of 1926, he went to the Red Lake area to check out a rush in the region. He turned down an opportunity to get there quickly and conveniently by plane. Instead, being a true Northern outdoorsman, he travelled by dogsled.

In his 1936 interview, McIntyre said he enjoyed his adventures in the Northland, whether he was at work or at play.

“Sandy’s earnings since 1903 have been tabulated well into six figures, but without qualm he admits that he is broke, and could he relive his life he would do exactly as he has already done. ‘Too much money is no good. It lasts too long and keeps a many away from his work. I never tried saving money and I don’t think I ever could. I like to work and the life of a prospector is the best a fellow can lead.’”

McIntyre’s efforts resulted in others making millions of dollars, creating employment opportunities for many and strengthened the economy of Northern communities. He was as tough as they come, worked and played hard, and died penniless, but with no regrets.

“You can’t take it with you when you die, your life is short and you are dead a long time,” McIntyre said. “If I had all to do again, I’d do exactly the same thing.”