This story was originally published on TimminsToday on May 31. It's being shared again today — the 80th anniversary of D-Day — for readers who may have missed it.

"It was a different world then. It was a world that required young men like myself to be prepared to die for a civilization that was worth living in."

--Harry Read, British D-Day veteran

Many will gather on June 6 to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Normandy, the battle that would position the Allies to end the war in Europe. While Allied Forces had begun to secure victories in Italy, North Africa and over the Atlantic, American Forces were pushing hard for an invasion of Western Europe, at Normandy, that would hopefully bring an end to the war.

Code-named “Operation Overlord”, a combined air-sea-land attack was organized to descend on occupied France. The “day of destiny” was scheduled for June 6, 1944. Troops from Britain, Canada and the United States were parachuted into Northern France while soldiers stormed the beaches of Normandy. The fighting was fierce and the casualties were devastating, but by the end of that day, the Allies had succeeded in setting up a bridgehead that would allow them to advance into France. The idea of setting up a second front was successful, German forces would have to fight Soviet Russia on one side and Allied Forces on the other — the writing was on the wall for the Third Reich.

The Battle of Normandy still counts as one of the largest naval, air and land operations in history. Figures from the day detail an invasion force that is still seen as impressive today: over 18,000 paratroopers were airdropped into France after midnight on June 6. Allied airmen flew 14,000 sorties in support of the landing; 7,000 naval vessels took part in Operation Neptune, escorting 132,000 troops onto the beaches of Juno (Canadian Forces), Gold and Sword (British Forces) and Omaha and Utah (American Forces).

The Battle of Normandy did not end the war, but it was successful in bringing about the start of the end of the European conflict. With the toe-hold established on the French beaches, Allied Forces finally found a path that would allow them to advance into the country but it was not an easy situation as German forces fought hard to keep their ground.

General Alfred Jodl, operations chief of the German High Command was blunt in his assessment: “We shall see who fights better and who dies more easily, the German soldier faced with the destruction of his homeland or the Americans and British, who don’t even know what they are fighting for in Europe.” Even with those sentiments, it became clear that Germany would not be able to sustain the fight on both fronts. By the end of August 1944, the German army was in full retreat; the Allies gleefully liberated Paris just before midnight on Aug. 24, when they reached the Hotel de Ville in the centre of Paris. (Ernest Hemingway was part of the press corps who followed the Americans into Paris and famously rocked up to the Ritz and declared it liberated – then proceeded to charge 51 dry martinis to his bar tab).

The Allied push lost momentum by September and the Germans rallied to regain some ground, but their counter-offensive at Ardennes in December of that year was a failure. Allied forces seized the advantage and continued on their march toward Germany, and ultimately Berlin, culminating in the end of the European portion of the war on May 9, 1945.

Timmins sent many young men and women to the front. Harry J. Murray of Timmins was one of those men who fought at Juno Beach, a battle that lasted from June 6 to Aug. 30, 1944. His sister, Kathleen Murray Caldbick, 12 at the time of the battle, wrote to the museum with Pte. Murray’s story:

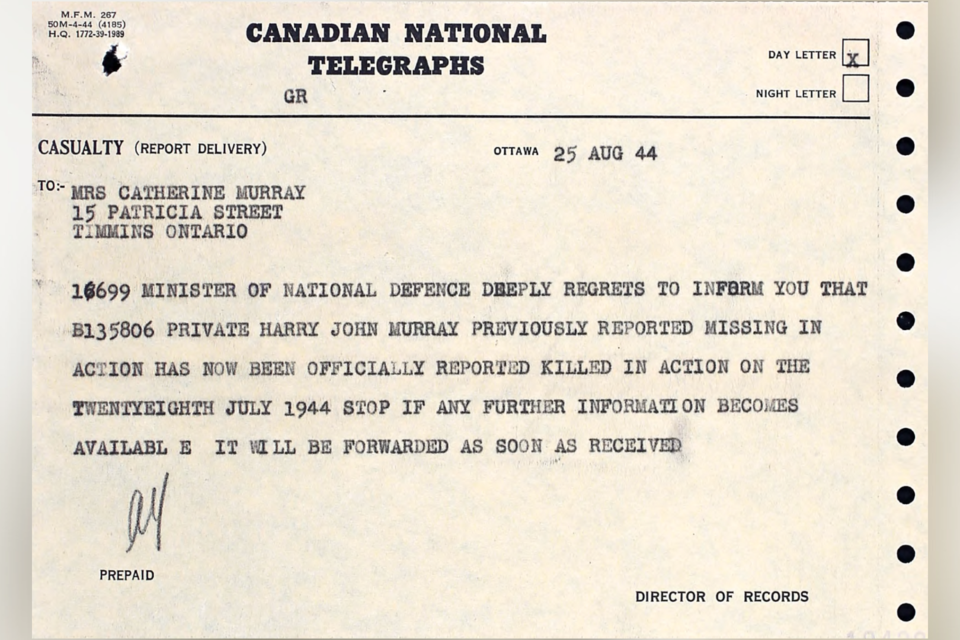

“My brother died in one of the most infamous battles of the Second World War, the Battle of Normandy, or D-Day. Only 15 men of the 320 in the Black Watch Division survived this particular tragedy. On D-Day, my father sat through the night till departing for work in the morning, ear to the radio, following minutely broadcast details of the Normandy invasion, knowing his son was in the thick of the battle. Two days later we received the telegram that Harry was missing in action, and three weeks later confirmation of his death. During those three weeks, our neighbours, the Browns, received news that their son Angus, serving with the Engineering Corps in France, was killed by American bombers misjudging their target and inadvertently bombing a Canadian base.

“Amongst the few survivors of the Black Watch Regiment was Todd Mahon of South Porcupine who was badly wounded and sent home. Although the official telegram listed Harry’s death on the 28th of July, a following letter from his Major said it was July 26th, and still another letter from a buddy who claimed to be with him when he died, said July 25th. Harry was buried Aug. 10th, 1944, at the Canadian cemetery at Bretteville-sur-Laize, near Caen, France. Mother steadfastly refused to visit the grave site.”