It is part of a history lesson we know little about, so perhaps we need a little schooling.

Envision hard rock miners, once toiling far underground in dark, cramped and dangerous conditions; it was arduous and risky work.

They emerged tired and dirty at the end of their shifts, walking back to small wood-sided homes and their immigrant families. Mining, along with forestry, created what was then called ‘New Ontario,’ -- what we know as Northern Ontario.

Indigenous mining in the north began after the last period of glaciations, people of the Plano culture moved into the area and began quarrying quartzite at Sheguiandah on Manitoulin Island. Mining is an important economic activity in Northern Ontario. It has been since the first copper mines at Bruce Mines in 1846 and Silver Islet in 1868.

Monuments are structures that pay tribute to the achievements, heritage, or the ideals of a person, group, event or time in history. Memorials are different. Like cenotaphs, they are built to honour and remember those who die for unselfish reasons; their names are present.

Not sure why I thought of this story. There have been many cemetery stories and story links to the natural and cultural heritage of the north. At the Canadian Ecology Centre we have staged, for more than a dozen years, free Teacher’s Mining Tours, bringing awareness through the lens of “seeing is believing,” and to the four pillars of contemporary mining: jobs, technology, safety and the environment. We know “if it is not mined, it is grown and if it is not grown it’s mined.” Maybe there is an appreciation of what was to what is? We learn every day.

But there are a number of mining memorials and exhibits throughout the north that bring attention to the sacrifices that have occurred in this industry. The installations are artistic and compelling, and so I discovered.

But first I needed some perspective. There are not many mining historians; I needed a teacher.

Stan Sudol is one for sure. He is a Toronto-based communications consultant, freelance mining columnist and owner/editor of RepublicOfMining.com – a mining news aggregator website. He is originally from Sudbury and worked at Inco’s Clarabell Mill from 1976-77 and worked underground as a summer student at Inco’s Frood-Stobie Mine in 1980.

He knows his history and why the economic history of northern Ontario is integrally linked to the mining sector.

“Much of the settlement patterns of the province’s north are linked to the discovery of the major gold mining camps. It all started with the Cobalt silver boom in 1903 with the construction of the provincial Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway to help colonize and economically develop the agriculturally rich clay-belt region of northeastern Ontario," said Sudol.

He starts his mining class with one example.

“The bitter Kirkland Lake gold miner’s strike of 1941-42 is one of the most important industrial disputes in Canadian labour history, a watershed struggle for union rights. In the United States, the Wagner Act of 1935 guaranteed workers the right to organize into trade unions and conduct collective bargaining. At the time, there was no similar legislation in Canada. On Nov. 18, 1941 roughly 4,000 workers walked out on strike. The mine owners held firm and Ontario Premier Mitchell Hepburn even sent 180 provincial police to keep the peace which angered and intimidated the workers. The strike came to a humiliating end on Feb. 12, 1942. While this was a bitter defeat for the workers, the strike galvanized the Canadian labour movement and heavily influenced Canada’s and Ontario’s wartime and post-war labour policy.”

It was a defining moment for the union movement.

“The rallying cry of “Remember Kirkland Lake” throughout the entire province and the close political ties developing between labour and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) political party (today’s NDP) forced both the federal and provincial governments to finally enact legislation compelling all employers to recognize unions fairly elected by workers and to bargain in good faith,“ Sudol said. "It was the beginning of the Ontario Collective Bargaining Act in Ontario and a federal Privy Council order, for the entire country.”

There is much to learn. I have become a student again.

Sudbury

The Sudbury nickel camp was discovered in 1883 due to the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railroad.

Stan shares another teachable moment:

"It would be the major source of this strategic metal for the American military industrial complex – tanks, jet engines, aircraft carriers - for much the 1900s playing a key role during the First and Second World Wars, the Korean and Vietnam conflicts as well as integral for the special stainless steels that allowed the U.S. to land men on the moon.”

The first hint of organized unions began after the War of 1812, when skilled trades, or “journeymen” are recorded as meeting in secret in Halifax. By the end of the Second World War, after a long period of actions and struggle, unions finally gained recognition in Sudbury. The Mine Mill and Smelter Workers Union became the representative of workers in Sudbury’s Nickel-Copper Industry. It was in the early 1960s when a dispute with the United Steelworkers (now USW) resulted in two representative bodies.

There are three mining memorials here and another surrogate one. Kim Komarechka, of the USW office, was helpful in getting me an “admit slip” to the Sudbury class.

“The Leo Gerard Workers’ Memorial Park in Val Caron was established by the City of Greater Sudbury, however, J.P. Mrochek, our WSIB Representative, was instrumental in getting the whole thing up and running, including compiling the list of workers who passed away from injury and occupational disease in the Sudbury area, (see their Facebook page)," she said.

Every June 20 is important to the members of Mine-Mill-Smelter Local 598-Unifor. On that day they honour four brothers who lost their lives in 1984 during a seismic event. There is a memorial at 2550 Richard Lake Rd. at their campground.

There is the Bell Park Sudbury Mining Heritage Sculpture or National Mining Monument celebrating the city's mining history. This impressive installation is a tribute to miners from the first prospector-old timers with their picks and axes moving to the depiction of contemporary mining; their collective work merges into two giant hands extracting what lies beneath the Earth’s surface.

As I was wandering around Bell Park this summer past, I found another small remembrance affixed to a massive slab of granite dedicated to the pioneer prospectors and geologists of the Sudbury basin on Oct. 6, 1966; it is located adjacent to the explanation of the Sudbury basin.

Elliot Lake

Sudol reviews with me the history here. During the 1970s, uranium miners in Elliot Lake became alarmed about the high incidence of lung cancer and silicosis.

“They went on strike over health and safety conditions. In 1976, the Ontario government appointed a Royal Commission to investigate health and safety in mines. Chaired by Dr. James Ham, it became known as the Ham Commission which made numerous recommendations that were adapted by the industry and resulted in the passing of the first Occupational Health and Safety Act in 1978 in Ontario.”

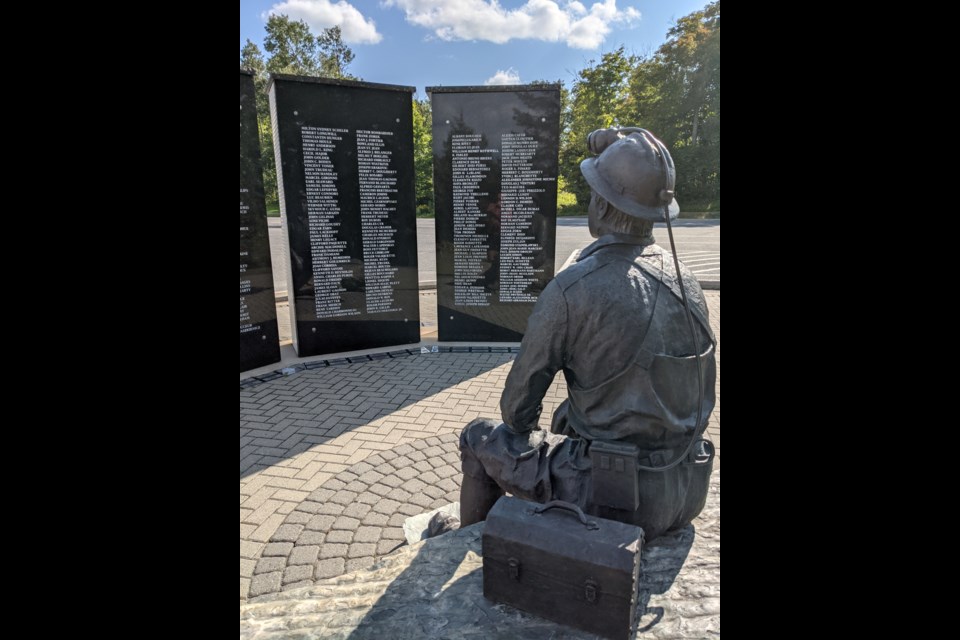

Elliot Lake's Miners' Memorial Park, located on the shores of Horne Lake, is home to the Mining Monument, the Miners' Memorial, and the Prospectors' Monument. The park is dedicated to the area's heritage and history of uranium mining. All of the monuments were designed and created by local artist Laura Brown Breetvelt (Timmins as well).

The Prospectors' Monument is the newest installment in the Miners' Memorial Park. This monument honours all of the early prospectors who staked our area and discovered uranium deposits. The Mining Monument provides information on the history of mining in Elliot Lake by celebrating the families who transformed a rural community into the Uranium Capital of the World. And the Miners' Memorial Wall is engraved with the names of workers from Elliot Lake's mines who have died from workplace accidents or occupational illnesses.

On Canada's Annual Day of Mourning, April 28, a ceremony is held at Memorial Park to commemorate the individuals being added to the wall and bring awareness to workplace safety and occupational exposures.

Kirkland Lake

Kirkland Lake owes its existence to the hard work of miners since the discovery of gold in 1911. The population reached a peak of nearly 25,000 at the outbreak of the Second World War, now a little less than 8,000. In honour of those miners, both living and those who have lost their lives, the Miners’ Memorial was erected on the former property of Sir Harry Oakes in 1994. The project was completed due to the grassroots fundraising of the Miners’ Memorial Foundation, chaired at the time by Steven Yee.

Charlie Angus, the Member of Parliament for Timmins-James Bay, has a new book called Cobalt - Cradle of the Demon Metals Birth of a Mining Superpower.

“The Kirkland Lake memorial was a breakthrough art installation because it showed the real work of Macassa miners in dramatic form. The artists Sally Lawrence and Rob Moir used real miners as their role models. What made it even more powerful was that it listed the names of the miners who died on the job. At the time there was some controversy about the naming of the dead as there were some who thought it would make the industry look bad. People, however, felt a deep affinity for this sculpture because it spoke to the sacrifice of northern families and gave dignity to those who were killed on the job. What we have not yet acknowledged through a public memorial are the thousands more who have died from industrial illnesses in the mines," writes Angus.

In another book, Mirrors of Stone: Fragments of the Porcupine Frontier, the MP points out that the only place where you can even begin to glimpse the massive toll of industrial illness on the working population of the north is to walk through the graveyards of Timmins. In the years prior to the Second World War the average life expectancy for an immigrant miner was a mere 41 years of age. It was the labour battles in Elliot Lake that led to the complete transformation of the health and safety standards of the workplace.

“The struggle of the Steelworkers in Elliot Lake, Sudbury and the northern gold mines transformed the standards for health and safety in all areas of work. “

Timmins

In the early 1900s mining operations in the region of Timmins-Porcupine became home to dozens of prospectors during the Porcupine Gold Rush. The Lions Club commissioned Laura Brown Breetvelt in 2007 to create the Porcupine Miner's Memorial as a tribute to many miners killed, to their families and to preserve the community’s mining history.

An underground fire in the Timmins Hollinger gold mine in 1928 killed 39 men.

Sudol continued tutoring me:

“The result was the creation of a provincial mine rescue service in the major camps and the continued evolution of the organization that has made the province a world leader. But other safety issues due to underground instability would claim many, many men and further safety advances would come only after unions were established and many hard-fought strikes won.”

This monument, in the shadow of the soon-to-be-refurbished McIntyre headframe is next to the famed McIntyre Arena, highlighted by a 10-foot bronze miner standing in front of an iconic granite headframe, accompanied by his family in bronze. It really is compelling and I think that is where my story lede originates. The names of 594 miners are engraved on a granite tribute.

Wawa

Mining came before the Wawa Goose. The 1897 gold fever that struck Wawa led to the unexpected discovery of iron ore in 1898. Rock samples made their way into the hands of Francis Hector Clergue, an American entrepreneur who at once recognized the ore for its potential in the form of a great steel empire in Sault Ste. Marie. This discovery transformed Wawa and the Algoma District. With the demand for steel and iron during World War II, a sinter plant was built in Wawa to treat the siderite iron from the Helen Mine.

Local historian and author of many books, Johanna Rowe said,”Wawa has no official memorial to the lives lost in the various mining ventures scattered throughout the mountainous landscape. But there are a number of significant mining related artifacts commemorating Wawa’s extensive gold and iron mining history. As the home of the last underground iron mine in North America, the Jumbo Drill and Mining Heritage Park at the far end of Wawa’s downtown core are a fitting tribute to the continued legacy of Algoma Ore and the many mines, miners and families that laid the foundation for our town. “It may be an impetus for a committee to look at a mining memorial.

Cobalt

There is a memorial plaque in downtown Cobalt next to the miniature headframe, and more according to Maggie Wilson, president of the Cobalt Historical Society.

“The name of the site is the Willet Green Miller Memorial Park (The first provincial geologist who is credited for naming the town Cobalt). Over the years as plaques and cairns travelled from one spot to another, they have eventually been collected here - more by accident than design. The site is therefore a gallery to the tributes bestowed on the Town, and is enhanced by mining relics such as the ore cart and the Moir art work.

“The Moirs were commissioned to work on a miners' memorial for Kirkland Lake. Their workshop was at the Cobalt train station. Remnants of this project (the casts of the sculpture) were used in the bas relief art installation on the outcrop on Silver Street, a continuation of the memorial park.”

The End of Semester

Stopping at any memorial you read the names; there may be a familiar reason. But for no other, know that at a mining memorial the departed are part of a proud heritage that goes beyond the often historical depicted mining tunnel, helmet and attached light, denim jeans, heavy leather boots and lunch box.

I do know now why I did this story.

“The working conditions in most of these mines were horrific by today’s standards,” said Sudol. “Through mining memorials we never forget the courage and sacrifices of our past generations.”

I used to get detentions in high school for skipping but I am glad to be in class this week anyway.

Here is the map of locations and I am sure I have missed some tributes and will look forward to hearing from the readers especially in the northwest as this summer was restricted (see this column and this one).